Chimtarga Pass

Chimtarga Pass (4760 meters, 15,617 feet), Fann Mountains, Tajikistan

Chimtarga Pass is a serious obstacle for trekkers and hikers (but not for climbers) who wish to do a connecting or loop route of the most popular lakes (Kulikalon, Alauddin and Buzurg/Bolshoi Alo) in Tajikistan’s Fann Mountains. On one day it may be simple and rather easy for an acclimatized trekker in good shape, and the next day it may be impossible and even deadly.

The following is a comprehensive guide to traversing Chimtarga Pass. It is not meant to be a brief or an enjoyable read. Rather, it is meant to contain as much useful information as possible. This guide is meant for those who have already done some reading elsewhere and have the vague outlines of a plan, and a map in front of them.

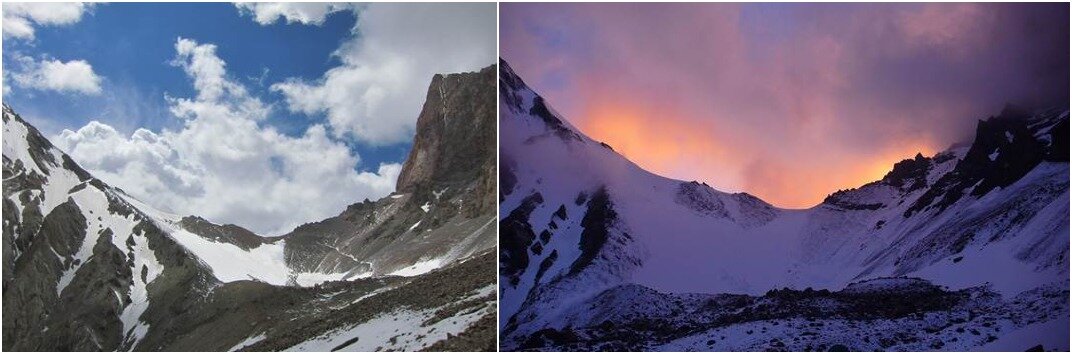

This photo above, via the Vargaftik 2016 climbing group, shows a view of Chimtarga Pass that you as a hiker likely won’t see. This is the east side view of Chimtarga Pass from a climbing route above Mutny Lake. Peak Energia on the left, and Peak Chimtarga on the right. This is the most ‘representative‘ view of the pass, as it was taken by a regular lens from a distance. Most other photos in this guide are smartphone camera photos, and they are wide-angle lenses that distort in several ways, one of which is to make the mountains look smaller and the distances shorter.

“Somebody told me it was easy…“

There are many conflicting accounts and single-anecdote reports on getting up and over Chimtarga Pass, so we have gone through hundreds of accounts, reports, videos and photos by hikers, trekkers and climbers from the last 20 years to come up with what we think is the most sound advice for those who want to hike through this 4760 meter pass.

So, you may have seen photos or videos showing an easy day on Chimtarga Pass, or you may have been told that it was no problem at all. For example, in the video below, a casually-dressed Russian trekking group on Chimtarga Pass enjoys the good weather while narrating a Lord of the Rings-themed trip (warning: rough language):

And then there is this hiking group below, wearing shorts and t-shirts (between the 4100 and 4400 meter camps) as they powered through from Mutny Lake to Bolshoi/Buzurg Alo Lake in a single day in August, with perfect conditions (photos and story via Sergey Broshevan, who guides Russian-speaking groups worldwide).

And here is a detailed video (in Russian) of a fair-weather trip through Chimtarag Pass in the second half of September 2024.

When I went through Chimtarga Pass on September 25, 2019, it was too chilly and windy for bare arms and legs, but I felt great and I had reasonably good weather, as can be seen in this 25 second clip from atop the pass.

However, if I—based on this one day—told people that going through Chimtarga Pass in late September will be problem-free, that would not be true. Weather is unpredictable, and you may not be as acclimatized as I was. This can be a very difficult pass for a variety of reasons. Accounts like these above may lead to a false sense of security. Chimtarga Pass can be difficult, and it can be dangerous - on any day of the year.

The Challenges of Chimtarga Pass

Elevation

Fresh Snowfall

Early Season Avalanches

Unmelted Snowfields in Mid-Summer

Steep, Rocky Slopes

Unclear Trail Sections

Assorted Difficulties and Annoyances (stream crossings, dogs, water, garbage, loud campsites)

Practical Difficulties (transportation, food, language, logistics)

Elevation: At 4760 meters, you can definitely experience serious symptoms of altitude sickness and fatigue (read about altitude sickness here). If you are coming fresh off the Pamir Highway, then you will be well-adjusted, especially if you stayed the night and did some hiking near Peak Lenin, Qarokul Lake, and Murghob. If you did something like the Bachor to Bardara trek in the Pamirs, then you are ready for 4760 meters. If you just flew to Dushanbe from somewhere near sea level, or if you are coming from Uzbekistan, then you will have to take it slow when it comes to gaining elevation.

For the clockwise route, I suggest (for reasons of scenery, practicality and acclimatization) not driving straight to the Vertikal Alauddin camp near lake Alauddin, but rather starting at one of the Seven Lakes (“Haft Kul”) or closer by at the Artuch Alplager (a hotel and camping complex). From Artuch you can do a half-day hike and spend the night at Kulikalon Lake or one of the smaller lakes nearby, then go over Alauddin Pass (3721 meters) to Alauddin Lake the following day. The next day you can go up to Mutny Lake (3500 meters) where there are many camping spots, or even onward to the informal camping spot at about 4100 meters if you are feeling good. If you are unsure about how good you feel, then you can spend an extra day at Mutny Lake and do an up-and-down acclimatization hike (you can view the routes above the lake on any map app that uses Open Street Map data). I would not camp higher than the 4100 meter camp. Those who camp at the 4500 meter camp without a long-term acclimatization routine usually regret it: altitude headaches, dizziness, sleeplessness.

The 4500 meter camping area (merely a collection of flat spots for your tent), nice enough on some days to wear shorts, but at night… Photo by Nunatak.

Aside from elevation sickness, the wind and cold at night also may be a problem. For example, the 2019 Kravchenko group (PDF report) stayed the night at the 4500 meter camp on August 14-15 and reported this:

At night, a stormy wind began…. Our tent was literally crushed, it's good that there were no collapses. The guys kept the second tent up all night using their arms. It was freezing at night, the water in the bottle froze. There was no precipitation, but the wind continued to… blow away everything that lay outside. The weather was not expected to improve. Climbing the mountain had to be postponed until the next time. The most difficult thing was to take down the tents in such a strong wind. We took this matter very seriously and everything worked out for us, and only one sit-pad blew away.

Of course, being well-acclimatized and with very warm gear, a storm-worthy tent, plus good luck with weather, can make the 4500 meter camp an acceptable spot to sleep (it’s usually the mountain climbers camped here, on their way up to or down from Peak Energia). Some of the mountain climbers even camp in the saddle of Chimtarga Pass itself, or rather just below the east side - out of the worst of the wind.

If you are going in a counter-clockwise direction (less common and less popular), then we suggest using an overnight stay at Buzurg Alo Lake (Bolshoi Allo) (3150 meters) and another one between 3500 and 3700 meters if you want to be cautious about acclimatization. The lack of a suitable campsite on the very steep west side between 3700 meters and the pass at 4760 meters is just one reason why the counter-clockwise route is not popular.

The good news? Despite some climbers and trekkers getting altitude sickness here, none have become completely debilitated and needed a rescue [please contact us if you know of a rescue and we will update this guide]. Of the anecdotes I have found, it usually involves a person with mild to moderate symptoms walking down to Alauddin Lake.

My personal anecdote (July 20, 2018) is this: I was not acclimatized, I had been in southern Tajikistan for a month. I took a car to the Vertikal Alauddin camp and then hiked straight to Mutny Lake at 3500 meters (Dushanbe 9:00am to Mutny Lake 5:00pm same day, that’s a 2800 meter difference). The next morning I felt surprisingly great, so I tried to go through Chimtarga Pass that day. Between the 4100 meters and 4500 meters camp I started to feel dizzy (I never feel dizzy). This, compounded by the fact that there was a very steep snow field leading up to the pass led me to turn back after sitting at the 4500 camp for a while. By the time I got to Mutny Lake (3500 meters) I felt perfectly fine, but I went down to Alauddin Lake just to be sure. The previous two times I had failed to get through Chimtarga Pass was due to one person in the group not being in good enough shape, and then another time when my travel partner was not acclimatized, and I ruled out an attempt after seeing his progress below 4000 meters. The fourth time I went alone and only after having spent two weeks in the Alay and Pamir mountains (a sure way to acclimatize). This time I felt perfectly fine and I had good luck with weather.

If, like on my unsuccessful 2018 hike, you start to feel the symptoms of altitude sickness, you can lose elevation very quickly here. Unlike many treks in the Pamirs (high plateau and high valleys), you can lose elevation quickly here in the Fann Mountains (steep mountains, low valleys) and get down quickly. All the medical rescues I know of are in the Pamirs, and none in the Fann Mountains.

If you are worried about elevation sickness, then head down to your doctor’s office and ask for a prescription for Acetazolamide (branded as Diamox in the US). It can prevent and reduce the severity of symptoms. More info here.

Fresh Snowfall: It can snow every single day of the year on Chimtarga Pass at 4760 meters. It can snow every single day of the year at 3500 meters in the Fann Mountains (including at Mutny Lake - check out this late season snowfall). That includes July, August and September. Some photos and videos may be in order to really emphasize that.

Dutch trekkers having a very rough overnight at the 4500 camp on the east side of Chimtarga Pass. September (day unspecified). Read their full story here.

And in this video below from the 15th of August 2013, you can see wind-blown snow that fell within the last few days (it unhelpfully accumulated on the trail). The French group reported delaying their trip and waiting at Mutny Lake for the weather to clear.

Alexandrov team (link to large ZIP file report)

August 25, 2014. The top photo is from about 4400 meters, and the bottom photo shows the team at about 4600 meters. They camped just below the pass (the tiny yellow/red triangle), but noted the bad wind overnight. Being mountain climbers doing some high passes and peaks, they would have winter gear. Don’t try to camp in the saddle unless you are similarly equipped.

Alexandrov team (link to large ZIP file report)

The Alexandrov team then climbed up towards Peak Energia the next day, giving a view of the saddle that trekkers won’t get. In the top photo you can see Chimtarga Pass with the west side still covered in snow. So be aware that a mostly snow-free east side does not guarantee a snow-free west side. But in the bottom photo (west side of the pass) you can see that when they eventually did go down, they didn’t have to go far before the snow disappeared.

Collage above via the Zelentsova climbing group. Top left is Mutny Lake, top right is looking up from the 4100 meter camp, and bottom left shows the view of the pass from the 4400 meter camp, and the bottom right shows the view going down the west side of Chimtarga Pass. These photos are from August 19-20, 2016, and they show what is probably not an uncommon scenario in August or September: the snowfields from the last winter have melted, but a light snowfall has come down. In these conditions (a light layer of fresh snow) I personally would go through without worrying about my footing (no need for crampons), but you should be aware of how water resistant/proof your shoes/boot are, as this may result in cold wet feet - not a situation you want to be in if you can’t get through the pass in a single day. Also, some of the rocky sections may be slippery - not enough to deter someone who is confident in variable weather trail conditions, but it may be a problem for others.

August 20, 2016

The Zelentsova group got snowed on at Mutny Lake, and then again the next day when they camped in Chimtarga Pass itself. So beware of repeat snowfalls, even in August.

The weather on July 29, 2011 was fickle. Lunchtime at the 4400 meter camp was clear, but by dinner time some fresh snow had fallen. Photos by a group of climbers from Dmitrov.

A near-worst case August scenario: August 22, 2015. Photo below via Pohod v gory. This group woke up to snow and 30-meter visibility outside their tents at the 4500 meter camp, and then experienced high winds and snow as they made their way up the pass.

Best case scenario below: August 9, 2016. Photo by the Vargaftik group (link to photos and report in Russian).

So, how about planning your trip around a weather forecast? That’s wishful thinking. There is not very good weather forecasting in the mountains of Tajikistan. And the mountains make their own weather, and aside from the (rare) big weather systems moving in and out at this time of year, there is usually just lingering high mountain clouds that give one mountain sunshine, and then the neighboring mountain a snowfall. What I can authoritatively say is that there is a reason that Switzerland and northern Kyrgyzstan are green, versus the yellow-brown dried grass color of the mountains of Tajikistan in August: it doesn’t rain very much in the mountains here, especially not after mid-summer. From all the reports I saw, it seems like there is about, on average, about a 30% chance of snow falling at Chimtarga on any one day in August, and even then it’s very light. I haven’t seen enough accounts of September to say anything for sure about that month, but in general September is as dry as August across Tajikistan. So I would expect the same.

Early Season Avalanches: You should absolutely not be here as a trekker or hiker in June. There will be avalanches coming down in the mid and upper sections on the east side of the pass (I’m not sure about the west side). I even found one account by Ukrainian climbers who saw the results of a very recent avalanche at about 4000 meters on the east side of Chimtarga Pass on July 21st, 2019.

Photos and story via Livejournal user SlooD.

Here’s a quick video clip of the aftermath of the same avalanche:

Now contrast this with my trip exactly one year earlier on July 20, 2018. At that time this exact spot was perfectly safe. There was no large amount of snow left in the avalanche danger slopes, and what had come down had come down weeks ago and mostly compacted and melted. Giving advice based on that one trip would obviously have been very dangerous advice for someone planning a trip exactly one year later when this avalanche occurred.

Unmelted Winter Snowfields in Mid-Summer: There is a bigger problem than (small amounts) of fresh snow: unmelted and compacted snow fields/patches left over from the winter. If you stay on the route that you see on any map app that use Open Street Map data, you will not need to worry about crevasses as you can easily avoid the glaciers on either side of the pass. But you can’t avoid snowfields in the earlier part of the season, and on steep slopes they can be dangerous.

So, aside from the avalanche danger in June and July there is the issue of the unmelted snow fields/patches that can persist even into August. Starting at about 3800 meters (just above Mutny Lake) you will likely need to walk across some patches of snow (and remnants of what was once a larger glacier). This is in a less steep area that the rest of the route and is safe and easy, aside from picking the wrong spot to cross a stream that appears and disappears. The problem is further up the pass. In July you will have to deal with steep snow slopes starting at the 4100 meter camp. These snow slopes, when compacted (melting in the sun and then freezing overnight) can send you down the mountainside like a waterslide. You could be launched down the slope and into the rocks. This is where crampons and an ice axe come in handy. Of course, you need to know how to use them, be comfortable walking in crampons in a variety of conditions, and have plenty of practice self-arresting a fall with your ice axe. If not, Chimtarga Pass is not for you until after this snow has melted (a light dusting of fresh snow on dry ground is much less of a worry, but it can still lubricate your fall down certain slopes).

Now, if it is right on the verge of the pass being free and clear (later July after a dry, low snowfall winter and a warm early summer, or early to mid-August after a heavy snowfall winter and a not-so-hot early summer), then you will probably be dealing only with the unmelted snowfields on the slope after the 4500 meter camp.

This photo above, from August 29, 2014 by the Shestak group, is the driest, most snow-free photo I could find. Don’t expect these conditions. This seems, based on my survey of available materials, to be a in once in a decade (or two) type of occurrence (although climate change may change that).

This photo below from August 19, 2008 shows perfect hiking conditions. There are some easily avoidable small snow patches at the 4500 meter camp down below in the right, and the final approach is completely snow-free. Photo via the 2008 Dombrovsky group.

The small snow patch that the red arrow cuts through just below the top of the pass is the remnant of a small cornice, which will be more of an obstacle to a hiker earlier in the year (but you can walk right around it).

My photo below is from September 25, 2019 when I passed through Chimtarga Pass without my boots touching any snow at all (except for the easy snow patches just below the 4100 meter camp). A clear trail goes not straight up the center (blocked by a snow field), but above and to the right (it can be seen faintly in this photo).

20 August 2010

This photo by a group of Ukrainian climbers shows that in a heavy snow year, there can still be unmelted snow patches in late August. The remaining snow here just barely blocks the trail right below the pass. If you cross a snow patch like this, know that one slip can send you down the slope at high speed (with rocks and boulders waiting for you at the bottom). Of course, this group was composed of climbers and they didn’t deem this little snow patch worthy of putting on crampons. But you should.

30 July 2017

Contrast the photo above to this photo by the Otachkin climbing group. The snowfields on the trail had melted completely by the end of July 2017.

19 July 2019

The 2019 Chugunov group (PDF link) walked by fresh avalanches between Mutny lake and the 4100 meter camp, and then started on steep, snowy and icy slopes right above the 4100 meter camp. This image show a person between the 4400 meter camp and the 4500 meter camp. The group recommends the use of crampons and ice axes (they met a couple at this camp with nothing but trekking poles). One slip and down the mountain you go without crampons and an ice axe.

What does Chimtarga Pass look like when it is completely blocked to hikers and trekkers? This video screenshot of mountain climbers from Belarus descending Peak Energia (on July 8, 2019) shows Chimtarga Pass in the upper middle of the image. What you see is, at a minimum, 600 meters of elevation of snow leading up to Chimtarga Pass from below. Full video here.

29 July 2004

There must have been quite a heavy snowfall in winter 2003-2004, plus a not-so-warm spring/summer. Still at the end of July almost the entire route is under the snow, including the section out of view that starts at Mutny Lake. Photo via the MTSU climbing group.

July 21, 2018

So far I have focused mostly on the east side of Chimtarga Pass, but the west side can offer some snow/ice-related difficulties. This photo from the Novosyolov group shows an icy couloir blocking their path about 200 meters below Chimatarga Pass on the west side. The entire group—all mountain climbers—put on their crampons and carried ice axes as they crossed. This photo doesn’t quite show exactly how steep this section actually is. A fall will send you down a few hundred meters in elevation very quickly.

July 19, 2019. Chugunov group (PDF link)

This couloir (a couple hundred meters of elevation drop) on the west side of the pass is, later in the summer, filled with scree and gravel. But in this photo it requires using ice axes and crampons, as the people here are doing. The photo is deceptive, you can’t easily go on the dry ground to the left or right. Above and below are obstacles that require you to stay in the couloir.

A view above of the west side of Chimtarga Pass, still covered in unmelted snow on July 29, 2004. Photo by the Ganakhovsky team from MGTU.

2020 was obviously not the year for travel, so I know of no technical reports by Russian climbers of Chimtarga Pass for this last year. However, Tajikistan did have extremely low winter (2019-2020) precipitation in the mountains, and a resulting lack of water in reservoirs. I assumed that this would mean that the mountain passes were snow-free very early in the season. I have a subscription to weekly Sentinel satellite imagery, so I went through the archives. My assumption was wrong. Completely wrong.

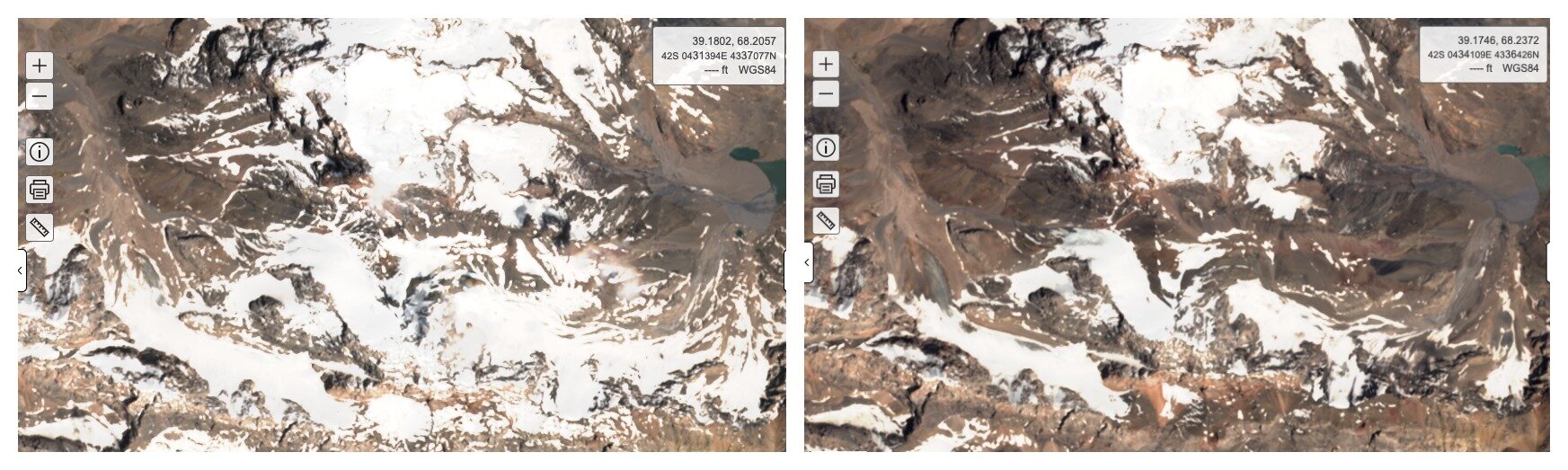

Top image August 10, 2020; bottom image September 10, 2020. Red dots in top image are Chimtarga Pass (left) and the 4500 meter camp (right).

2020 would have been a bad year for trekkers who don’t like steep snow fields. In mid-August a trek through the pass would have involved a steep snow field on the east side, and steep, snow- and ice-filled couloirs on the west side. By mid-September the east side would have been a snow-free trek, but the west side still had a snowy couloir to cross. One Tajik group went through at the beginning of August (plenty of snow underfoot), and 10-year-old climber (below) went up and down the east side just before mid-August (wind-blown snow and a big drift/cornice in the pass).

Obviously, amateur meteorology is not going to help you plan a trek through Chimtarga Pass. What accounts for the presence—or lack of—snow fields on steep slopes and in couloirs in the summer trekking season on Chimtarga Pass? The level of winter precipitation? The temperatures in spring and early summer? The type of snow that falls and how likely it is to come down as an avalanche or stay on the slope? Sub-regional variations in weather? Variations in weather from valley to valley and peak to peak? A combination of the above? Other factors?

What’s clear is that this is not some ski resort in Colorado or Switzerland where they can accurately predict the summer hiking season based on what sort of snowpack they see in the winter and spring. There is no meteorological station at Mutny Lake watching the mountain all year. Plan for unpredictability when it comes to snow.

Can an experienced hiker with crampons ignore our advice and go long before the snow melts? Sure, you can check out a photo essay of someone who went not just up Chimtarga Pass, but to the summit of Energia with crampons and trekking poles. But the author’s bio reveals an extensive background in mountaineering at high altitude. So they really knew what they were doing and decided to take the risk of no ice axes, ropes, harnesses or helmets. I would suggest only getting on the snow if you are experienced in crampons and with an ice axe.

Can you make it on the snow without crampons, maybe even while wearing running shoes? Sure, anything is possible. And plenty of people do this on many routes worldwide, but it is putting you in danger. Check out a (6-weeks too early) descent of nearby Kaznok Pass by a group in shoes. Or check out these tourists in northern Italy, over 4000 meters and dressed for the shopping mall.

Steep, rocky slopes: Snow aside, some trekkers may have problems even on completely dry slopes. Those who are accustomed to hiking on well-built and maintained trails in Europe, Nepal, Patagonia or in national parks in the US or Canada may be in for a surprise. Nobody has designed and built any trails here. Nobody has built any switchbacks (zig-zags) on steep slopes (unless beaten into the ground by donkeys and sheep), sometimes the trail just goes straight up.

How will you do on these trails and routes? Taking an example from Kyrgyzstan, I observed Kyrgyz porters going down the steep, rocky east side of Alakol Pass in 10 minutes. And then I saw some tourists doing it in 20 minutes. But then I saw some tourists taking 90 minutes. Finally, I went back up Alakol Pass with a French trekker to help her friend, who needed to have her hands held by a Kyrgyz guide as she shuffled down the slope, shaking and in tears (while I carried her backpack). Which category do you fall in? If you are used to rough scrambling or off-trail hiking, then you have little to worry about. But if you are on the opposite side of the spectrum, Chimtarga Pass could be a struggle. I can’t imagine any of those who struggled on the rocky slopes of Alakol Pass to get through Chimtarga Pass, which is almost 1 kilometer higher.

I’ll start first with the west side, which is seldom talked about aside from people remarking that they would rather go down this side than up it.

The photo above from the 2016 Vargaftik group (August 8) shows the westside couloir that starts at about 4250 meters and ends at about 4000 meters (imagine this under snow and ice). The further down you go, the more accumulation there is of loose gravel and scree. This type of terrain divides people: some can actually run down it, some hate it and go super-slow. Don’t believe me that running is possible? Well, it’s more like fast-walking. I did it in this couloir, and it was the quickest elevation drop I’ve ever done on foot. Here is a video demonstration on Youtube, from a group of Russian trekkers descending from Chimtarga Pass (running starts at 3:37). And below is another, briefer example of running down loose scree on the west side of the pass (starting at 10:59).

Your comfort in loose, rocky terrain affects how quickly you will get up and down, and perhaps is an obstacle for those who are on the wrong end of the spectrum I described above. More realistically, your problem will be falling hard on your rear or back. I fell hard on my butt once on the west side. There are some spots below the pass and before the couloir where the ground has solid, angled rock with a light covering of gravel on top. It doesn’t matter how nimble you are and how good your balance is, you can slip on this surface quite easily. I suggest going slow and using trekking poles when you come across this type of surface. I can see how a fall onto your ass may result in a bad cruise, contusion or even an injury.

This photo by the 2016 Vargaftik group (August 8) shows, at the bottom of the photo, the type of trail on which you can slip and fall on your rear on the west side of the pass. It’s a little steeper than the photo shows. Good news: on the west side there are very few and very short sections where you might fall further off the trail.

There is nowhere on the east side trail where a slip and a fall on a rocky surface will send you far down the mountain, except for one rocky ledge above the 4100 meter camp (check the route on any app using OSM data: there are two routes marked, take the one to the right/east if you want to avoid this ledge area and the drop-off section it has). If you pick the correct route, you’ll be on safe sections like this one below on the east side (photo via TrekRussia, check out their full photo report):

Full article and photos on TrekRussia.ru

Unclear Trail Sections: Some hikers don’t do so well with trails that fade, disappear and reappear. And some are confused when there are multiple trails leading to the same place. First of all, you should have a phone with an offline map app, and with Tajikistan downloaded for offline use. This will tell you if you are going the wrong way.

The sections that are unclear start at about 3800 meters, right above Mutny Lake. Here the route turns a corner and you walk alongside the Eastern Energia Glacier. This area is not very steep and snowfields linger here well into the season. As for the glacier, it doesn’t have a clear defined edge, it sort of fades into the rocks. So you may be walking on a route you think will be all rocks, but then notice ice underneath. In this area, which continues up close to the 4100 camp, there is no single, correct route. And you won’t always see a clear trail. People choose different routes based on the conditions and their preferences. Maybe they would rather walk on a snow field than on a gravel moraine.

One of my photos, at about 3900 meters. No trail to be seen, but plenty of routes to choose as you go directly up the valley towards the 4100 meter camp. Walking on melting snowfields and large rocks does not result in a visible trail.

After the 4100 meter camp there will soon be two or more routes to choose from (clear, obvious trails once the snow is melted) until just below the 4400 meter camp. From here there is only one trail/route until you are well down the west side of the pass towards Bolshoi Allo lake. It seems easy on the west side at first, as you figure the trail must just stay at the bottom of the gorge/valley, but there are a few spots where you go up a side slope a little ways. The trail fades when it goes across areas that get washed away every spring, and in some areas with boulders where a trail won’t get beaten into the ground. There are also, above and below Buzurg Alo Lake (Bolshoi Allo), some trails that go the wrong way for a while, beaten into the ground by 50 years of tourists going the wrong way.

I wish I could say you can just use the map on your phone to avoid this, but you are in an east-west gorge and the GPS here is not so great. It occasionally jumped around and showed me in a location I know was not possible. It does this again in a few spots below Buzurg Alo Lake. I know it is not just my problem, as I’ve looked at a number of different GPS tracks by hikers who have all stayed on the same exact trail, and sometimes their GPS tracks/waypoints conflict drastically in these locations, in some cases by over 100 meters. I think it’s because in the gorge you no longer have a clear line of sight to the GPS satellites at this latitude (or some such technical explanation).

Photo at top by the 2019 Chugunov group (PDF link). Photo at bottom mine, also 2019. This is on the west side of the pass, halfway between Chimtarga Pass and Buzurg Alo Lake.

The photo at top was taken after the third week of July, and mine was taken after the third week of September. These photos of the same spot (one up close and one from further away) shows why no trail is visible. The clear route is what I did: a quick hop over the narrow stream and down the valley on an easy, flat gravel surface. But every year during snowmelt, any sign of a trail is washed away or filled in with sediment.

Assorted Difficulties and Annoyances (stream crossings, water, dogs, garbage, loud campsites): First up are the stream crossings. There is one right after Mutny Lake that flows into the west side of the lake, which can be avoided by going through the boulder field on the east side of the lake. Or you can take off your boots and roll up your pants and walk across this small, safe stream. An early morning after a cool night may result in a stream that you can jump or step across. After 3800 meters on the east side if you stay too far to the left/south side of the gorge, you may have to get across a small but annoying stream. It’s very narrow and you should be able to find a place where you can step across without taking off your boots. Or, like I did, you can find a snow bridge that the stream flows under. On the west side of the pass there should be no streams worth worrying about after July (but your will likely have to take off your boots once before Buzurg Alo Lake, and once further down the gorge after the lake.).

The stream on the west side of Mutny Lake, July 20, 2018.

I took this photo in the morning after taking off my boots and walking across the stream. Later in the day it does get bigger, but not by enough to make crossing a difficulty. In September the next year the stream was low enough to step across even in the later afternoon.

On the topic of water, you’ll need to drink some. Consider the 4100 meter camp your last chance to fill up on water until you get down to about 3800 meters on the west side of the pass and reach the right tributary of the Zindon River. Occasionally people do say they find water at the 4500 meter camp, but these people seem to be there in July or early August. Later visitors report it to be dry. I’m sure it does, like the snow cover, vary from year to year. But it’s best to play it safe and fill up at 4100 meters. Also, a lot of climbers do camp at 4400 and 4500 meters, and it’s not a large area. I’m not sure where exactly they decide to use the toilet. You don’t want to fill up on water and then see toilet paper fluttering down from uphill — water filter or purification tablets aside.

Dogs come with the shepherds and flocks. They bark like they want to murder. But that’s all they do (but that fact never really comforts you when 6 large dogs with facial scars come out to greet you). Dog attacks are very rare, and I don’t know of any tourists being bitten or attacked—just scared (2025 edit added: a trekker in the Fann Mountains was bit in the leg). However, the area between Alauddin and Mutny Lake is very marginal grazing land. I haven’t seen grazing happening here in July or August, and I have not seen any complaints about them from other hikers (compared to several complaints from the Archamaydon Valley). But I did, in late September, pass by a very large flock of sheep and goats coming down from Mutny Lake. How often do they come? How long do they stay? Do they avoid the tourist high season in July/August? I don’t know. I’m not sure about that. So I have my one single anecdote: there was a large flock of sheep and goats and a shepherd camp near Mutny Lake on September 25, 2019. One of the shepherds came out to say hello and escorted me past the camp, where 8 angry dogs loudly threatened to kill me as I walked by. Do you have a phobia of dogs? If so, I’m sorry. Tajikistan may not be the place for you to hike.

Garbage. I used to think it was just the Russian trekkers and climbers, but I looked closer at the garbage left at Alauddin, Mutny, Chimtarga, Bolshoi Allo and the locations in between. While there are the usual signs of trekkers from Russia and Ukraine: empty bottles of cognac, canned fish tins and fully-squeezed mayonnaise packs (and even some receipts from Russian supermarkets), I have also found products from British supermarkets, and expensive trekking food packages with American labels, plus evidence of many other countries’ citizens littering here. And then there are the Tajik employees of the tour companies. They too leave their garbage behind. So it’s everybody.

As for the camping spots, not everybody has the same sleeping schedule. A group may stay up and talk loudly well after you want to fall asleep. I would like to say that the mountain climbers police this, as they always get up very early, but they can be rather selfish: demanding utter silence at camp the night before they go up, and loud as a disco in camp after their successful climb. Local employees of the tour companies enjoy chatting, and talking loudly into the late evening and night is not—in local culture—considered to be rude or an impediment to anybody’s sleep. Also, how social are you? How much privacy do you want? I want silence and privacy, so I don’t camp at Alauddin or Mutny if I see a crowd. I camp at Piyola Lake if it’s not occupied, and I set up camp on the opposite side of Mutny Lake from where the many camping spots are located. Buzurg Alo Lake (Bolshoi Allo) in high season (late July to end of August) may occasionally get busy. I had it to myself at the end of September, but if I go in August I will probably camp (on the west side of the pass) in one of the many flat areas at about 3500-3550 meters or the final camp at about 3800 meters.

The photos above show the area around 3500 meters on the west side of Chimtarga Pass. Photo on the left by the Kulagin team on August 28, 2016 (looking up the valley). Photo on the right by myself on September 25, 2019 (looking down the valley). There were plenty of camping spots (flat areas for a tent, and water flowing nearby).

Practical Difficulties (transportation, food, language, logistics): Going with a tour company takes care of all these problems. Paramount Journey is a good local option for that, and they have a trek that includes Chimtarga Pass, and they will turn back from the pass if they think it will put you in danger, like any good outfit should. But if you are wanting to do this independently (for budget or other reasons), you will need to start doing your research on Caravanistan and buy a copy of Trekking in Tajikistan (the e-book weighs nothing and fits on your phone).

Speaking Russian or Tajik makes things go smoothly with the drivers. English won’t be of much help to you here, with the drivers or on the trail. Even the Artuch Alplager and the Vertikal Alauddin base camp are Russian-speaking operations (Russian, Ukrainian and eastern European trekkers and climbers dominate in this area) [2023 note: Artuch Alplager now has a manager who can speak some English]. As for food, be warned that things shut down in September, even though there is at least a full month of good weather remaining. Buying food at Vertikal, Alauddin Lake and at the cafe/store between Bibijanat and Kulisiyoh lakes will no longer be possible. So bring all the food you need. For more help on the practical considerations, check the two links above. And expect prices to have increased from what you see online, as the Tajik currency has depreciated in value.

Vertikal Alauddin has an announced last day of operations on their website (September 5th in previous years). And this base camp should not be relied upon in the high season, as they prefer to work with large groups of Russian-speakers with reservations, not random solo travelers or small groups who show up unannounced. They may be full. But if they aren’t, they’ll take your money. Just don’t expect guesthouse/homestay treatment. Artuch Alplager is opened for a longer season, and they are more accustomed to smaller groups of independent travelers who speak no Russian/Tajik.

Fees and permits? No permits, but you do need to pay a per-day fee to the forest ranger (lesnik in Russian, jangalbon in Tajik). It’s not a flat entrance fee, but rather calculated per day. You can pay this fee at Alauddin Lake (not the Vertikal Alauddin basecamp), and by one of the camps by the smaller lakes near Kulikalon. I forget the exact amount, something like 19 Somoni per day per person (but the last time I paid was 2018, the price may go up). If you don’t see anybody, then your visit is free. I’ve paid about 50% of the times I’ve visited (compared to 100% of the time at Iskandarkul). Also, bring your passport, as the fee-collectors will also register your information.

How about donkeys? Can you just put your bag on a donkey and have him/her do the hard work on Chimtarga Pass? Probably not. For donkeys, Mutny Lake (east side) or Bolshoi Allo Lake (west side) is the last stop, except for one guide named Said who can get his donkeys to the 4500 meters camp on the east side of Chimtarga Pass. The tour companies will know him (he’s not sitting around the lower lakes waiting for customers), but his services will likely be in demand in the high season.

One of Said’s brave donkeys coming up to the 4500 meter camp, mid-August 2017.

Photo via Peremena Mect.

Maps: The Russians generally use the Fann Mountains map layer created by Slazav, either on paper or electronically. But it’s in Russian. English speakers should go for an OSM-based offline map app on their phone and download Tajikistan for offline use (plus pay for the better version that has topographical lines and regular updates). Some maps are not good enough. For example, MAPS.me has the routes and the campsites, but it does not show the passes, nor list their names, and it doesn’t have any usable topographical lines (and it doesn’t clearly differentiate between a bridge and a ford). Other map apps are useful, but only if they rely on regularly updated Open Street Map data. But note the warning above about the inaccuracy of GPS in the gorges above and below Buzurg Alo.

Pass ratings: If you use the OsmAnd map app or if you are searching online in Russian, you will find ratings in parentheses after the name of the passes. In OsmAnd these are still in the Cyrillic alphabet. This is from the Soviet/Russian grading system for mountaineering routes. From easiest, the rating are: н/к, 1А, 1Б, 2А, 2Б, and upwards. Anything from 2 to 6 is absolutely not for a hiker or trekker. The easiest rating, н/к, is n/c, or ‘not classifiable‘ as it is too easy for a grade. This means that there is a hiking trail through the pass and no obstacles whatsoever. Alauddin Pass is an example. The next grade up is 1А, and this is a type of pass that offers no worries once the snow is melted. There may not be a defined trail, and it may be a little rough/steep. But there is no need for ropes, ice axes, crampons, etc. And you won’t need to put your hands on the ground or on rocks. Examples of passes like this are Dukdon and Sarimat, technically easy passes elsewhere in the Fann mountains that offer no obstacle to a trekker in good shape. Chimtarga is 1Б, and this is at the level where it’s clear that this mountaineering grading system doesn’t work for trekkers anymore. A 1Б (1B) pass is, for mountaineers, technically easy. But some 1B passes require you to be roped up in a harness with a team and using your crampons and ice axe while going around crevasses and bergschrunds. And some 1B passes can be walked through in running shoes (Chimtarga Pass in perfect conditions). Some 1B passes are no problem for trekkers, and some are impossible. So don’t rely on this rating system (aside from ruling out anything from 2-6). Rather, you should consider н/к and 1А passes to be easy once the snow has melted, and a 1Б (1B) pass to require some investigation to determine if a trekker can do it or not, and what equipment they will need.

Place names: The maps here all rely on the maps made during the Tsarist and Soviet times. Some mapmakers took the job seriously, but then the Russian-speaking tourist groups arrived in about the 1950s and started to give names to passes, lakes, and mountains without consulting the locals. So, if you speak to other tourists, guide companies, and locals who work with tourists, don’t worry about it. But if you can speak Russian or Tajik and you start talking to shepherds, villagers, firewood cutters or others, know that they may have different names. Mutny Lake? Mutny (мутный), also seen as Mutnoe, Mutnyi, etc. is a Russian word meaning muddy or turbid. The locals who don’t work with tourists have a different name. Same goes for other lakes. Bolshoi Allo has an obvious Russian word in the title, and did you know that there is a Chimtarga Lake? The shepherds do (it’s nowhere near Chimtarga Pass). And Maria Peak? Maria is not a Tajik name, obviously, nor is Energia Peak next to Chimtarga Pass. Below Mutny Lake I spoke in Tajik with a shepherd from Sarytag (real Tajik name: Saratoq) and told him I was going through Chimtarga Pass. He had never heard of Chimtarga Pass (the locals only named the passes they take animals through or that they used themselves). So if you talk to certain locals, don’t be surprised if the place name you say confuses them. There are differing opinions about which lake is actually Alauddin Lake, for example. Another shepherd pointed at various peaks and gave me their names, which were about 80% conflicting with the names given on the map (by Russian mountain climbers).

And then there is the issue of transliteration (writing a name in the Latin alphabet). Should it be written from the Tajik, or from the Russian? The Russians change Tajik spellings this way: O often becomes an A, the GH (‘ghayn’) letter becomes a G, the soft H becomes a G or a KH, the hard Q becomes a soft K, sometimes I becomes a Y, the J becomes DZH, and other similar changes. So, when doing your research, you may see Archamaidan (Russian) or Archamaydon (Tajik), Gushor (Russian) or Hushyor (Tajik), Gazza (Russian) or Ghazza (Tajik), Iskanderkul (Russian) or Iskandarkul (Tajik). And then there are just complete mistakes, such as the village of Saratoq by Iskandarkul Lake being named Sarytag by the Russian mapmakers. So if you don’t find much on your first Google search, it may be because of the variant spellings. Other issues may have nothing to do with the Russians. For example, it seems that long-distance Uzbek-speaking shepherds may have renamed areas that already had names in Tajik given by the Tajik-speaking villagers who lived nearby. So a villager and a shepherd may disagree on a name.

The government recently (2023-2024) clarified some placenames. The lake known to Russians as Bolshoi Allo is now officially Buzurg Alo.

Direction of Travel: Yes, most people do the route that includes Chimtarga Pass clockwise as that offers the most ease of acclimatization over several days or more (starting from Artuch or Haft Kul). Also, if you go counter-clockwise and you have to turn back from Chimtarga Pass due to weather or snow conditions, then you have to backtrack quite a long way to see the areas around Alauddin Lake and Kulikalon Lake (the most popular spots). Failing to get through the pass going clockwise is way better than failing while going counter-clockwise. Also, many people feel that the west side of Chimtarga Pass would be terrible for an ascent due to the loose rock and scree and steep chutes. I don’t exactly agree, but I am clearly in the minority on this issue.

How long will it take? When I went through Chimtarga Pass in 2019, I went from Mutny Lake to Buzurg Alo (Bolshoi Allo) Lake in 10 hours, including regular breaks and one hour in the pass enjoying the view. I was fully acclimatized from my very recent visit to the Pamirs (with a one-day break in Dushanbe) and I was in decent shape at the time. I would guess that if the Russian mountain climbers put on a backpack as light as mine, they would beat me to Bolshoi Allo Lake by maybe 2 hours, as would a good athlete (e.g., long distance runner). But some people take up to three full days for Mutny-Bolshoi Allo, especially those who need to be careful about acclimatization. They usually sleep at the 4100 meter camp above Mutny Lake (it’s a short trip from Mutny to this campsite, so don’t bother leaving too early in the morning).

Gear advice: The closer your sleeping bag rating is to -10 Celsius (15 Fahrenheit), the better. Of course, the trade-off is that you will be way too hot in that sort of bag at lower elevations in the Fann Mountains. For clothing, prepare for the worst: wind, snow and -5 Celsius. But the later you get in September the colder it will get.

Waterproof everything. A rain cover for your backpack (or an internal liner). A waterproof shell/jacket or poncho. Waterproof overpants (also nice when the cold wind blows).

As for the ice axe, any cheap and light ice axe will work for you as a hiker.

Many of the ’semi-rigid’ mountaineering crampons (‘C-1‘ in UK terminology) can be found in online reviews by someone using them on non-mountaineering hiking boots, but then the company websites usually say to only use them on mountaineering boots. Some online guides, such as this, are cautious about these type of crampons on flexible hiking boots, as they assume that you will be in crampons all day in all sorts of icy terrain and glaciers and that you might be tempted to do some sort of technical ascent. But some companies are OK with their crampons being strapped to a variety of footwear, such as the Black Diamond Contact strap-on crampons. You need to do your own research on the crampon issue, and ideally do some testing/practice. Mismatched crampons-to-boots can be both a comfort and a safety issue. Start with the REI crampon ‘how to‘ if you are new to crampons, and then Google from there.

If you are not familiar with the type of crampons that are more commonly used with hiking boots, you need a type of crampons that will work with (soft and flexible) hiking boots. Do an online search for ‘flexible,‘ strap-on’ crampons, or ‘hiking’/‘trail‘ crampons. Even then it seems that the manufacturers are pushing you towards using these crampons with rigid boots. But our concern here is merely getting across snowfields and the occasional patch of ice. And it’s clear that trail/hiking crampons (with less aggressive and shorter teeth) like the Kahtoola K10 and Hillsound Trail Pro are being used successfully on non-technical, not-climbing terrain (e.g., crossing a snowfield laterally on a steep slope, or on flat ice) with many types of soft, flexible hiking boots and even hiking shoes (the Kahtoola K10 crampons clearly work for early summer snowfields in the High Sierras, for example).

Are you wearing not boots, but rather runners? Then search for ‘traction devices‘ and ‘micro-spikes‘ for shoes. Of course, these don’t give you the same sort of traction/contact as crampons, but they are definitely better than bare shoes.

Some of the above-mentioned gear can be rented in Dushanbe from the Archa Foundation.

Final Advice: If you read carefully, you now understand that things are very unpredictable, and you can, as a hiker or trekker, be blocked from going through Chimtarga Pass on any day of the year. There are no guarantees. And even under the best of conditions, there are still some dangers and challenges. For the best chance of success, based on what can be seen across over a hundred accounts from the last 20 years, it would be best to wait until August (the later in the month the better) or September, and to show up with crampons and an ice axe (you can rent these from the Archa Foundation in Dushanbe, along with other camping, trekking and climbing gear). And don’t ignore the need for acclimatization to the elevation. If you are fresh from low altitudes, take your time gaining altitude (read this guide for the most-cautious approach to avoiding altitude sickness). If you ignore some or all of this advice, then please be open-minded to turning around and going back down the mountain if you feel bad, if there is too much snow still on the ground, or if it starts falling from the sky. Getting stuck up high in the cold can be deadly. And don’t rely on the climbers for help. They are not your personal rescue service, and they probably won’t be there after the first week of September. But if they suggest that you go down or turn back, you should listen.

Nota bene: I chose all the photos above based on their technical usefulness, not on their beauty (even if some are quite nice). The point of this guide is to give advice for getting safely through Chimtarga Pass, not to convince you to go. But if you haven’t already been convinced, then I find these links to include some great photos and videos from the Fann Mountains loop that includes Chimtarga Pass: Link 1, Link 2, Link 3, Link 4 (all in Russian, but Google translate can help with the photo captions). For a good look (in English) at what it is like for an acclimatized and in-shape hiker (who must struggle with language and transportation difficulties), check out this Youtuber’s 3-part series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3. And like suggested above, use Caravanistan and Trekking in Tajikistan (the e-book weighs nothing and fits on your phone) for all the logistical and practical information for getting to and from this area.

Update, 8 July 2021:

Winter 2020-2021 saw record low snowfall and there was a warm spring and hot summer with low precipitation in Tajikistan (and in the surrounding region). As a result, the snow melt is the earliest it has been in decades, and many areas that are usually still under snow are now snow free. The satellite comparison below shows 8 July 2021 (right) and 8 July 2019 (left), with 2019 being a normal year for snow levels.

2021 will probably be the best year for hiking through Chimtarga without walking on much snow, and therefor no need for crampons and an ice ax. You will, however, still need to worry about fresh snow, and that can happen at any time (whenever the current drought breaks).

2022 update: A bizarre summer of unusual weather occurred in the mountains of Tajikistan, and in other parts of the country. Short intense rain storms occurred throughout the summer, as opposed to ending in late spring or very early summer. If this repeats in future summers, then do not consider later July and August to have the usual likelihood of little to no precipitation in the mountains.

2023 update: More extreme weather - short intense heavy (and unusual) rainfall occurred in July and August. This means a heavy snowfall if the precipitation hits you up high. This may be the norm, and previous weather patterns may no longer be relied upon.

2024 update: This year was not an extreme weather year like the previous two years. Chimtarga Pass was doable for trekkers (and snow free, minus very light snowfall) from mid-August until very late until mid-October. Don’t count on visiting in mid-October in most years.