Tajikistan Mountain Advice: Information and Warnings for Hikers/Trekkers

There are some unique characteristics of - and specialized advice for - each particular mountainous area of Tajikistan. For the Fann Mountains, Yaghnob and the Pamirs, check out the guidebook Trekking in Tajikistan, and for a Pamirs-specific set of advice, try to find a copy of Tajikistan and the High Pamirs, or visit the website it was based on. It’s a decade out of date, but much of the advice still applies.

For specific gear, health and food advice, read our long article here.

General Mountain Advice for Tajikistan

Weather

Elevation

Shepherds, flocks and sheep dogs

Yugan

Crevasses

Rock fall

Food poisoning and drinking water

Rivers

Wild Animals & Vermin

Taxis

Who to call in an emergency

Placenames

Dress code

Gear replacement

1. Weather: Weather, as with all mountain weather worldwide, is unpredictable. Often a sunny day in Dushanbe is matched by rain or snow in the mountains just to the north. Check out the weather site Meteo.tj, but understand that this government agency focusses on weather mostly in populated areas, and it does not have the resources of a European meteorological agency. That disclaimer aside, even the wetter areas of central and western Tajikistan have less summer rain than the mountains of Kyrgyzstan near Bishkek and Issyk-Kul, for example (the eastern Pamirs are the driest). And certainly in summer you’ll encounter less rain in the wettest mountain areas of Tajikistan than in the European Alps and the Pacific Northwest.

How about storms? Well, they do happen. Bring a good tent and not just a rain-proof jacket, but also rain-proof pants. Mountain rain will give you hypothermia if you don't have dry legs. What storms need to be watched for? A cold rainy system that comes down from Russia (usually into western and northern Tajikistan). They don't often happen in the summer, but when they do, they bring rain and cooler temperatures to cities like Dushanbe and Samarkand, and very cold rain and high winds to the mountains for a couple of days. This contrasts to the isolated small storms and rains that you can usually expect in the mountains - these don't last long. June and July are the stormiest in the mountains, with August and September being drier.

Don't have waterproof gear? The Archa Foundation rental store in Dushanbe has rentals.

Tajikistan is not as cold as Kyrgyzstan, being farther south and away from northern weather systems (but this is not so much the case in the highest areas of the central and eastern Pamirs). Daytime temperatures in the mountains range from 5 to 20 celsius, with as high as 25-30 at lower elevations near some of the trailheads. In 2023 at the low point near the end of a trek I encountered a record setting heat wave in the high 30s.

How cold can it get? Expect at worst a few degrees below zero (Celsius) at higher elevations overnight during the summer. There is no need to sleep up high in a pass unless you want to (for fun). Be extra cautious in the eastern half of the Pamirs, as it can far get colder here and once on the plateau there are no low areas to descend to to camp for the night.

Summer snow? Yes, at the highest elevations and in some of the high passes (above 3500 meters). But usually there is little accumulation and it doesn't last for long, especially on the south-facing slopes. There are no snow storms during the trekking season in Tajikistan on the scale of a dangerous Himalayan snow storm.

I suggest, in addition to a good set of warm mountain clothing, a sleeping bag rated to about -10 Celsius (if you are going above 3500 meters), and a warm sleeping pad/mat to match (check out Thermarest’s discussion of the industry standard “R-Value“ measurements of warmth, and this Youtuber’s criticism of these measurements). Below 3500 meters you can get away with a -5 Celsius bag, and maybe even a 0 Celsius bag for those that are “warm sleepers.“

2. Elevation: As for elevation, its effects are unpredictable and altitude sickness affects people at random, regardless of their athletic conditioning. The most popular passes are in the low 4000s and high 3000s. The Pamirs have more passes above 4500 meters, while in western Tajikistan the only really high trekking pass is Chimtarga Pass in the Fann Mountains at 4700 meters. An advantage of western Tajikistan (basically, everything west of the central Pamirs) is that, unlike some areas in the central and eastern Pamirs, you can quickly get to a much lower elevation (mid-2000 meters) if you start to feel the symptoms of elevation sickness. In the Pamirs, there are sometimes no lower valleys to get to quickly, resulting in all known altitude sickness rescues in Tajikistan being in the Pamirs, and never in western Tajikistan. Examples include a very fit group of young trekkers and a group of world-class kayakers. Each of these groups had a single member who fell badly ill and needed a rescue. It can even happen to casual day-hikers.

What every tourist with mountain sickness in Tajikistan has in common is impatience and a tight schedule. They clearly do not want to slowly gain altitude. They want to get to spectacular high mountain scenery as quickly as possible.

The highest pass that a trekker will do in Tajikistan is about 5000 meters. Beyond that and you will be dealing with dangerous glaciers, deep snow and cliffs on mountaineering-only routes.

Note: when researching altitude sickness for trekkers, you should ignore most of the rescue stories from Nepal, as those are usually insurance scams perpetrated by local guides, medical clinics and helicopter companies. No such practice exists in Tajikistan, where your guide or the government agency responsible will exhaust all potential solutions before getting a helicopter or a hospital involved. Note: this does not apply to Russian mountain climbers, as the relevant government agencies are well aware of the high altitude rescue insurance that they all have. They dispatch helicopters to them quite quickly as it provides a good pay-day.

3. Shepherds, flocks and sheep dogs: Overwhelmingly, shepherds are your friends. If you are in distress and need help, head towards a sheep camp. If anything, shepherds are perhaps too friendly. Russian expeditions in isolated areas frequently mention the difficulties in having to refuse multiple offers of hospitality, starting with tea and ending with a full meal of mutton. If you accept every offer, you will never reach your destination on time and as planned. This is, as can be expected, not much of a problem in the popular areas such as the Fann Mountains, the most popular Pamir hikes, or near the tourist areas of Varzob. But in more isolated areas the shepherds are bored and quite happy to see a rare stranger. If you are in a hurry, take the offer of tea and decline the full meal. If the shepherd appears to be busy with a flock, by yelling "chai!" he probably means for you to visit his camp at the end of the day once the sheep are fed and ready for a night's sleep. He may be too busy to serve you tea. But note that in some of the warmer mountain areas, the shepherds graze their animals in the early morning and in the evening, avoiding the heat of midday. So some shepherds are free from about 10am to 4pm.

Shepherds in western Tajikistan don’t often drink alcohol while in the mountains. And if they do drink, I would expect them to be even more friendly. The two slightly intoxicated shepherds that I (middle-aged foreign male) encountered on separate occasions in the Fann Mountains were quite jovial and wanted me to join them for a drink. In other countries (that I won't name) there is a small but noticeable problem with drunk shepherds who can be aggressive.

Are shepherds 100% good people? Absolutely not. A shepherd on a rarely trekked route in eastern Tajikistan stole a woman’s boots from under her tent while she was sleeping and then another shepherd tried to rape her while she was searching for her boots the next day. To be blunt, something like this (attempting to rape a shoeless foreign woman in the mountains) is unthinkable in a rural mountain Tajik, Uzbek or Pamiri region of Tajikistan. But this was not in an Uzbek, Pamiri or Tajik area. In some ethnic Kyrgyz communities, bride kidnapping and regular sexual violence are common - and men from neighboring non-Kyrgyz communities have started to emulate their behavior.

Do shepherds steal? Aside from the boot theft above, I only know of a theft of two tents in a non-tourist mountain area of Tajikistan (with either shepherds or firewood cutters as the only suspects), a titanium cooking pot being stolen by passing shepherds at Alauddin Lake, and one unlabelled food cache being raided in the Fann Mountains. The “thief“ may not have known what a food cache is and why it is done, perhaps believing the food was lost or abandoned - which is why the Russians climbers leave a clearly written and dated note on their food caches explaining that this is not abandoned food/supplies. This does not always work, as one group lost most of their food cache to shepherds while on a climb between Wakhan and Shakhdara.

I believe that theft of camping equipment is far more common in North America and in parts of Europe. But to be safe, don’t leave your bag, your tent and your gear unattended (e.g., while you do a day hike in the middle of a longer trek). Losing your gear (tent, sleeping bag, extra clothing) on some routes can be a death sentence.

Do shepherds know the mountains well? Yes, sometimes they have their valley memorized and are an amazing source of information (with exact information about the best location and time of day for a river crossing, for example). However, some only know their own small area. I have talked to shepherds who helpfully tried to offer information about passes that was dreadfully wrong: "Yes, no problem. You can walk over that pass" (I most definitely could not, it was a 2B Soviet/Russian-graded mountaineering pass) or "On the other side of that pass is the Rasht Valley" (Rasht was 200km in the opposite direction).

Sometimes the shepherds are not locals tending the village's animals. Depending on the sub-region or district, they may be contract shepherds far from home and the flocks of animals are owned by some far-off businessman who has grazing rights in the mountains.

Some shepherds can speak Russian, but Russian expeditions are giving them poorer grades every year (a broad trend in rural Tajikistan). So you may need to speak Tajik, but this may not help with some women and kids in the Yaghnob Valley (Yaghnobi speakers) and with the younger goat herders in parts of the western Fann Mountains (who may be Luli, Magat or from some other Roma-type community who speak their own dialect). All the men, however, will speak some Tajik (including the ethnic Uzbeks). The language advice above does not apply to Pamiri and Kyrgyz speaking areas in the Pamirs (but many Pamiris can at least speak basic Tajik).

Shepherd dogs. The dogs are less friendly - far less friendly. “Central Asia Shepherd Dogs,“ sometimes referred to in the west as the “Alabay“ breed (their name in Turkmenistan), are known in Tajikistan simply as “Shepherd Dog” (Sagi Chuponi or Sagi Dahmarda). They often look frightening, with cropped ears and tails, and an occasionally scarred face. They are a member of the flock and they assume you are a threat until you sit at their camp with their masters for a while. They are mostly just about barking, and they reserve their attack mode for strange dogs, wolves, bears and other predators. They will, however, chase you off sometimes (as opposed to staying in place and barking). I have been chased, but they stopped once they were satisfied I was heading away from the sheep. They have also stopped when I stood my ground.

I have not heard directly about any confirmed sheep dogs attacks on trekkers or climbers that resulted in a bite injury (that does not mean that it hasn't happened), so they may be “all bark, no bite.“ But one guide from Samarkand who works in the Fann Mountains said at least one hiker was bitten on the leg.

The dogs calm down once the whole flock is on the move and on a road. But in the more isolated areas if I see a flock coming or I see that I will be soon walking through one, I do my best to spot the shepherd and head toward him or at least try to catch his attention. He knows what to do. He will probably come out to greet you while waving off his dogs. Sometimes it seems like he is not in control of his dogs, and he will swing his stick or throw rocks at them. But this is normal. They are are not like some well-trained guardian dog in the Italian Pyrenees, but they will stand to the side as the shepherd escorts you through the flock.

These are my experiences in the two videos below.

The part where I got my knife ready was because two different groups of dogs had been fighting each other before they set their sights on me. I was worried that dogs in the middle of a dog fight may be unpredictable. But in the end they acted just like all other dogs I encountered.

If you want to see a real expert in action, check out the very small boy in the black jacket deal with camp dogs in this video starting at 5:15.

Right of way. Sheep, donkeys, cows, horses and yaks have the right of way. Goats can be negotiated with (it’s easier for them to safely jump off the trail). What you don't want to do is block a narrow trail when the flock is going up or down. You may scare them into going the wrong direction or even off a cliff. Get out of the way, as far away as possible (and expect dogs to be nearby). Don't make the shepherd's job any more difficult than it is. If you are going down a glacier or snowfield and a flock is coming up, get completely out of the way (but not sideways into a crevasse): scaring a sheep off the track that the shepherds have cut through the snow/ice can mean death for the animal. If you stop any of the animals, they will be trampled by the ones behind. Animals die in the high passes regularly. See Anatoly Sharipov's post on animals dying on Mura Pass (in the Hisor/Fann region). The same applies for bridges and narrow trails next to dangerous rivers: get out of the way, and even better go back the opposite direction until you find an open area.

Note that the right of way and the right to graze includes your tent. One trekker had curious cows destroy his tent in Kyrgyzstan, and I had to twice scare off a curious cow in Tajikistan who kept pushing its nose into my tent.

Shepherd-less animals. Cows, yaks, donkeys and horses are left on their own to graze - sometimes for a full summer without a shepherd checking up on them. So you may see these animals and there won’t be a shepherd anywhere nearby. In some places the cows will return to an unmanned stone corral or shelter every night on their own. Sheep and goats need a shepherd and dog protection. So goats and sheep mean a shepherd, a camp and dogs are not too far away.

In isolated areas you may come across the bulls (the dairy cows are usually down below being milked). The bulls here are much, much friendlier than range cattle in the US and Canada. However, at night they seem to be less friendly. In one gorge the bulls were moving at night and when they saw my tent they got scared/angry and started to bellow while slowly approaching my tent (multiples times during the night). What you need to do is get out or your tent, show them that you are a person and herd them away. Yes, in this case (below) I was camping at what turned out to be their nighttime spot. But the rocks and terrain didn’t allow for camping anywhere else.

Women at shepherd camps and small villages. There are some mountain camps and summer villages that are tended by women and children (the men may be out herding, at a high camp, gone below for supplies, working in Russia or doing other work in the village). Stopping for a visit or a break is not appropriate for men. If you don’t see an adult man or an older teenage boy, keep walking (no photos, don’t try to chat, etc.). This applies especially in Tajik areas of Tajikistan. An exception is for women trekkers, as the local women and girls love interacting with foreign women. Women and girls in rural areas are far less likely than the men to speak any Russian. For Pamirs advice, check the links at top.

Despite my own advice, I have had very insistent grandmother-aged Tajik women demand I sit down for tea, bread and yoghurt. If a grandmother appears to be in charge and insists multiple times that you sit for tea, you should probably comply. Some places are far more accustomed to foreign men, such as the summer village at Chuqurak Lake above the Artuch Alplager.

In decades past, local women were generally OK with foreign women taking their photo. This has changed, especially in western Tajikistan. The arrival of social media in Tajikistan has made women and girls more vary of their image being loosed onto the internet. Only take their photos if they (adult women) show enthusiasm and approval.

Requests from Shepherds and villagers. Plenty of people have been at a summer camp/village and had children, women and/or men ask them for something. A Russian climber with lots of experience in Tajikistan stated that almost all requests fall into three categories: head, stomach, and sun. Basically, they are asking for pills to relieve headaches, pills to relieve a range of stomach problems, and sunscreen. Another Russian climber noted a 4th category, and this request should be obvious: cigarettes. He wrote that his team carries a pack of cigarettes even though nobody on the team smokes. But based on my time with shepherds and villagers in mountain towns, cigarette smoking is far less common than nosvai/nasvai, a snus-type powdered tobacco that is stuffed under the lips/cheeks. You will recognize this product locally as being sold as a green powder in a tiny plastic packet.

Gifts and payments. Shepherds will feed you and 100% refuse payment. Many villagers in areas that don’t see tourists often will also feed you and house you for the night. They too will likely refuse payment. As for the trick of being sneaky and leaving behind cash for the host to discover later, a guidebook written based on experience in the 1990s is the source of that tactic. This has led to several instances of kids being sent on a run to catch up to tourists to give them the cash that they “forgot.” If I feel that a family is poor and really needs the money, I will give it to them in person and strongly insist until they take it. But this is becoming rare, as Tajikistan is nowhere near as poor an desperate as it was 30 years ago. Also, I find that I am often funneled/directed towards a relatively prosperous person in the village as a guest.

Gifts are far more acceptable, and quite welcome as I have found. A souvenir from your country is usually the best thing to give. I carry small country flag patches (the type backpackers used to collect - either velcro-backed or glue-on), and local people seem quite enthusiastic about taking them from me. Flags that are too common may be a little boring (Russia, China, USA). In this case, bring a state/regional flag or a sports team patch or something like that. The “cheesier“ the better (i.e, French flag with the Eiffel Tower is better than a simple tri-color). Any other souvenir from your home country that is light and portable will also suffice. If you’re a woman, I suggest bring some mini lip-balm for girls at remote shepherd camps and isolated villages (chapstick or any kind of SPF or moisturizer lip balm).

Drones. Technically, drones are illegal in Tajikistan if they have not been registered (in some Byzantine, mysterious registration process). But many local and foreign tourists still use them. You may want to consider not flying your drone anywhere near sheep, goats, donkeys, cattle and horses. Stampeding livestock can cause broken bones and miscarriages. Even worse, you may panic them into stampeding into a river or over a cliff. Once you’ve killed $10,000 worth of livestock, the shepherds will definitely lose their friendliness. As for wildlife, it’s illegal/immoral to harass wildlife with a drone in Europe and and North America, so don’t do it in Central Asia. Flying your drone over a lake or river can cause birds to abandon their nests, or at a minimum you are harassing exhausted migratory birds that are taking a break while crossing the mountain range. As for other animals, a foreign tourist chased a herd of Marco Polo sheep without consideration that this not only presents the danger of broken legs and miscarriages, but may have forced them to abandon a grazing area while hungry, forcing them on a long journey elsewhere. Don’t be this guy.

4. Yugan (Yughan/Юған): is a pretty green plant at mid-elevations that looks like young dill (and has yellow flowers in its mature phase). Yugan is a member of the Apiaceae (or Umbelliferae) family, and it is phototoxic. The sap of the plant combines with the sun to give your skin a chemical burn (phytophotodermatitis). It will sting badly, and the pain and blisters will last for days. Black hyperpigmentation scars then remain on the skin for about 6 months or longer. This is only a problem at mid-elevations at the beginning of the summer (May/June/July) until the plant dries out and becomes harmless. However, some areas with moist ground (next to a stream or in a gully) may have green yugan longer into the season. The plant does not grow in the driest areas of eastern Tajikistan. Avoid problems by not wandering into the high grass and vegetation or bushes, and by wearing long pants. You shouldn't be wearing shorts anyways, as they are not culturally appropriate for the villages you travel through. More information on avoiding yugan here.

5. Crevasses: Stay off of the glaciers to avoid dying in a crevasse or bergschrund. For treks that involve a glacier crossing, follow the exact specific advice that is available for that route. If no info is available, do not go on the glacier unless you are experienced with glacier travel.

6. Rock fall: Tajikistan is falling apart geologically. There is quite a bit of loose rock here, and it does fall down the mountains occasionally. Pitch your tent in an area that does not appear to have any fresh-looking loose rocks sitting around. They may have arrived at high speed from a higher elevation. And while scrambling, keep in mind that you may send loose rock falling below you. Be aware of who and what is located downhill.

7. Food poisoning/sickness and drinking water: Food poisoning happens at guesthouses, hotels and restaurants, but mostly at the cheap roadside cafes (usually the milder version that requires a free toilet to be nearby). One tour company stated that despite all the precautions they take, 1/3 of clients get mild to moderate stomach problems in Tajikistan. But if you are cooking for yourself while camping then you have no worries. As for general travelers, I’ve only ever known two people who had it bad enough to require a visit to a hospital (but surely there have been many, many more). Get travel antibiotics from your doctor at home.

Being a vegetarian is no protection from stomach illness, as you can get ill from fruits and vegetables. My technique for not getting sick when in a town or city or on the road? —> bananas, apples, bread, ramen, chips, nuts, junk food. If I must eat in a roadside restaurant I usually order soup (“shurbo“) as it has been thoroughly boiled or plov (pilau) as it has been similarly thoroughly cooked. Avoid salads, vegetables, melons, strawberries, fruit that is hard to wash (grapes, cherries), chicken, minced/ground meat, and any mixed plate dish (I trust neither the meat nor the vegetables). This is no way to live if you are an expat who lives long-term in the country, but this is a reasonably cautious approach for the short-term visitor who does not want to spend most of their vacation on the toilet. You have far less to worry about in Dushanbe.

As for water, bring a filter or some sort of chemical treatment. Once I’m at a high altitude above the grazing areas and camps, I drink directly from small streams. Elsewhere, I drink unfiltered spring water. The cautious approach is to still filter these water sources. The safest option is to bring not a filter, but a purifier (purifiers also get heavy metals, chemicals and viruses, so it’s useful as a general travel tool when viruses and pollution are a problem in towns, cities, agricultural and industrial areas). But do you really need a purifier? Read this article or this article for more information. I no longer carry a purifier. I just use a regular filter (the Sawyer Squeeze or something equivalent), and then add a chemical treatment to the filtered water if I’m worried about viruses.

8. Rivers: Local people do occasionally drown in Tajikistan's mountain rivers. Do your best to not fall into a river while fully clothed and wearing a backpack. As for fording a river or stream, we are mapping fords. However, we do not map fords that require a rope and harness (i.e., on the bigger rivers and dangerous steep creeks). Those shortcuts are up to you. The mountain water will get you quickly: it’s extremely cold, and very fast. Even knee-high water can be a disaster if you slip and fall. The alternative if there is no bridge? We’ve mapped the routes up and down the rivers to spots where the river is smaller or there is a snow bridge. So you may end up going up and down a river for a couple of hours as opposed to a quick crossing.

9. Wild Animals and Vermin: Encounters with bears, wolves and snow leopards are rare in Tajikistan, and they are quite shy. There have been a few rare attacks and deaths in the Pamirs by winter-starved wolves, but not in the summer.

As for bears, a forest ranger in a northern mountain region claimed that he was attacked by a bear, but this was likely a cover story for his son hunting a bear that then turned on him (he has since been charged by authorities for poaching). Within the last decade there have been a couple of confirmed bear attacks in Tajikistan. One attack on a villager gathering nuts in the mountains (that may have been provoked by his dog), and an attack on two teenage firewood gatherers. Neither were fatal. Outside of online media reports, the local people often report attacks as having occurred in the area - but over a very long period of time. In other cases, accounts of deadly bear attacks turn out to be false. One online account of a deadly attack on a shepherd defending his sheep in Kuhistoni Mastchoh is reported on only one website, many years after the attack (2014). However, not being able to find a confirmed deadly bear attack online does not mean it has not happened. The internet and the reporting by local authorities in Tajikistan is not very thorough.

The most dangerous place to camp in terms of bears would be near a shepherd camp. The bears and wolves come close at night to try to find a stray animal at the edge of the flock. So what you need to do is to camp right next to the shepherds (within about 20 meters of their tent), or very far away (1km would be sufficient).

2023 update: First confirmed bear attack on a tourist. A trekker woke up to a bear dragging her tent. She got a superficial paw-swipe wound on her hips and needed a few days of recuperation before hiking again. Story on Instagram.

As for food safety, there is at least one account of a climbing team’s cache of food being raided by a bear while they were up on a glacier. He/she ate everything but the canned food.

Snow leopards? Two attacks in 100 years across Central Asia, so don't worry about them. There is, however, a mythical yeti-type creature that may or may not eat humans, but they exist only in the vivid imagination. There are also a host of other spirits, jinns, and supernatural forces active in the mountains, but they are neutral in regards to trekkers.

Mice exist, and from anecdotes and what I’ve personally seen, they can be expected at mountain shepherd huts and large shepherd tents. I’ve seen them in both huts and tents that were actively being used by shepherds (thanks to the infinite supply of bread crumbs), and others have seen them at huts that have been long abandoned for the season. I’ve never seen them while camping in my tent far from villages and shepherd camps. As for rats, I’ve never seen them or heard any second-hand anecdotes about them in the mountains. I think the shepherd guardian dogs would hunt and eat them if they tried to migrate to the mountains (or perhaps there is not enough food for them in the mountains of Tajikistan).

10. Taxis and drivers: This is the #1 danger in the region, especially if you use the shared taxis instead of hiring a private driver. Usually I have a calm driver, but occasionally I get an aggressive guy who needs to be somewhere quickly. Nothing can be done about it, aside from speaking Tajik/Russian and making a deal ahead of time with the driver for a slow journey through the mountains. But this does not protect you from other drivers.

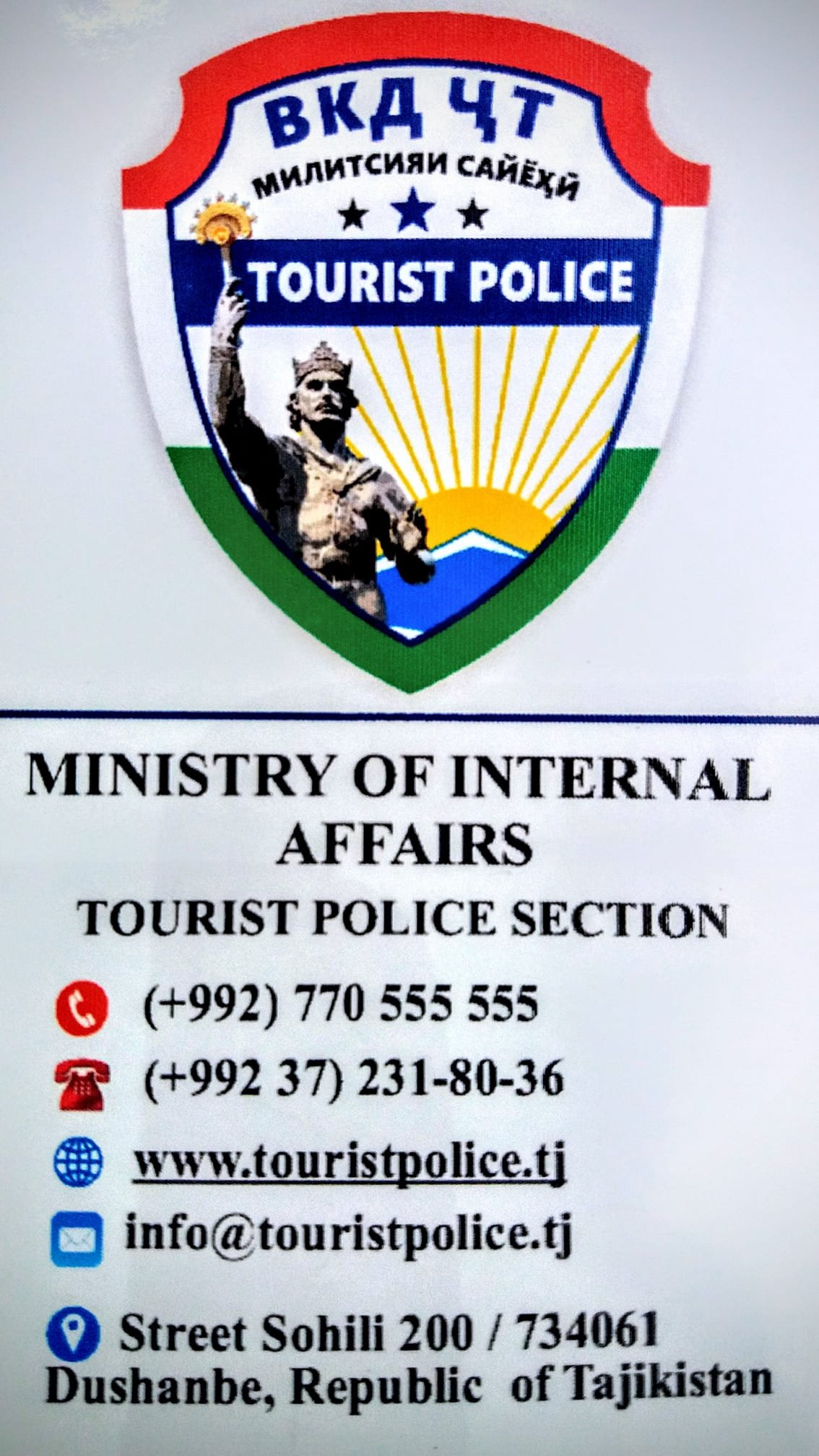

11. Who to call in an emergency: Obviously you won’t be making a call from the mountains (unless you have a satellite phone). You can, however, text or email the Tajikistan Tourist Police from a satellite SMS device (Garmin, Zoleo, etc.). Once back to a place where you have access to a phone or the internet, you can contact the Tajikistan Tourist Police (for emergencies). They speak Tajik, Russian and English, and should be your first point of contact if you are in some sort of crisis. Find them on Facebook or call them at: +992 77 055 5555. You can also call your embassy if you have one in Tajikistan, but the help they offer differs radically from embassy to embassy (from extremely helpful to downright useless). Note that even if your country does not have an embassy in Tajikistan, there may be another embassy that has an arrangement to offer you emergency consular services and assistance (for Europeans, this may be the embassy of France or Germany, for example).

Save this image to your phone:

When you add the number above to your phone, a contact for the Tourist Police will appear in Whatsapp and Telegram.

How well do the emergency buttons on your satellite device work in Tajikistan? I don’t know the exact brands, but multiple people over the last decade have pressed the button and the people at the other end (Gharmin or Zoleo or whoever) were able to then get in touch with the relevant authorities in Tajikistan and direct them to the location.

12. Placenames: The government regularly changes the names of regions, towns and villages, while the locals may continue using the old names. Some names are written phonetically, while some are written properly (example: Shaydon versus Shahidon, Khudgif versus Khudgiv). Either style may appear on the map. Sometimes villagers and shepherds use different names than what you see on the map. Sometimes the villagers and shepherds disagree with each other. Sometimes a village may have nickname that sounds very little like its proper name. Sometimes a river changes names upstream. But where? And according to who? Some passes have different names (Russian mountain climbers’ names versus the local names).

And then there are the repetitive use of common names throughout the country: five villages named Langar, all of which have trekking trails starting/ending there, in addition to the other Langars. But if you plan ahead of time and stick to your itinerary, you should be fine. However, some of the tiny hamlets may be mislabelled - in a few instances the source maps contradict each other. So there may be the occasional erroneous name/location on the map. All names on maps that appear on maps sourced from Open Street Map data use the official system of transliteration in Tajikistan (with variations for ethnic Pamiri and Kyrgyz names), not from Russian. Many other maps still use Russian transliteration (e.g., Murgab instead of Murghob, Kulyab instead of Kulob, Khojent instead of Khujand, Khorog instead of Khorugh etc.). So if you can’t find a placename, it’s likely there on the map in a different spelling.

2023 update: the government official changed thousands of names of natural objects (rivers, glaciers, mountains, passes, gorges, pastures, etc.). Read here to find out more.

13. Dress code: Play it safe - no shorts or bare shoulders in villages or at shepherd camps or in farmlands (for either gender). All regions have stricter clothing requirements than Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. This rule applies less so in the popular hiking areas of the Fann Mountains or the Pamirs. Wear what you want when you are in the middle of nowhere, but change back to culturally appropriate clothing when you get near a village. Your punishment for wearing shorts will be administered by yughan (read #4 above). When in people’s homes you must wear pants (even if the roadside guesthouses on the Pamir Highway tolerate people—cyclists usually—in shorts).

Don’t be weird. Wild beards like those seen on cross-Eurasia cyclists or on American long-distance thru hikers are not appropriate (e.g., the type of beard seen on some mentally ill homeless men). Locals who are very close to the most popular tourist routes have grown accustomed to seeing them. In the more remote regions you will scare people, as some will think you are either mentally ill or an extremist. Look at the beards that local men have. Old men get longer but tidy beards, younger men trim their beards (and even then they have problems at university and in government offices as their beards are not welcome).

Don’t wear black-on-black. Of your pants, shirt/top and backpack, only one item should be black. Fully black clothing is OK in the city if it’s black jeans and a black leather jacket or a suit, but in some remote areas you will look - at a distance - like one of two things: the security service’s elite special forces team, or a terrorist. I’m not joking. Ignore advice you get from people in the city on this.

As for camouflage clothing, leave it at home. You will see some shepherds and mountain villagers wearing camo jackets and even sometimes pants, but this is usually their old kit from their military service. You should not wear camo as a foreigner, unless you are a hunter being baby-sat by your local guiding team.

Have many people visited Tajikistan’s mountains in some sort of camo gear and had nothing happen? Sure, quite often. But I was with a group and a plainclothes security officer appeared out of nowhere in a village and was very angry that my friend had a jacket with 20% of the material having a camo pattern. So probably someone saw us and made a phone call regarding the foreign soldiers who just appeared out of the mountains.

14. Gear Replacement: In Dushanbe you can often find camping gas, some cheap & heavy sleeping bags, foam sleeping pads, and a very small tent selection. And this entirely depends on the continued operation of a single camping & hunting store and their stock on hand (plus occasionally there is camping gas for sale at City Hostel or Green House Hostel). That’s it for now. If you destroy your inflatable sleeping pad, you can go to the construction material section of any larger regional town bazaar and buy insulating wrap. It is closed cell foam with thermal foil reflective material on one side. You may need to stack two or more layers if it is thin. The seller will cut it to size for you. For gear and baggage storage in Dushanbe, I would only trust a family-operated guesthouse. City Hostel has a room for storing bags - this is where I leave my extra gear while in the mountains (replacement shoes, extra toiletries, town clothes, etc.). For a full range of gear advice, read this.

Advice for women? Check out Adventures of Nicole’s advice for women in Tajikistan and Caravanistan for advice region-wide.