Maps, Navigation and Route Planning Tools for Mountain Exploration in Central Asia

Maps of Central Asia’s Mountains and Hiking Routes

If you go exploring in the mountains of Central Asia and you blindly follow the map on your smartphone app, or the paper map in your hands, you might die. Or more likely just be inconvenienced at the very least. You will do fine on popular routes that are well travelled. But these are few and far between in Central Asia. Everywhere else you should not trust the maps to be up-to-date or fully accurate.

Just because your map shows a bridge over a river does not mean that the bridge will be there when you get there. Just because your map shows a trail up a gorge does not mean that you will find a trail or even be able to go off-trail and find a route without being blocked by a cliff or large tributary river.

The information collected here is not targeted at day hikers on short routes or even for those doing the most popular multi-day treks in Central Asia. For these short and usually predictable routes (Alakol to Altyn Arashan, Ala Archa, Heights of Alay, Traveller’s Pass, Kulikalon and Alauddin Lakes, etc.), you can continue to use whatever offline map app you are already using. And by “map app“, I mean an app that is targeted at hikers and trekkers. Google, Apple, Bing and Yandex are useless for hiking in the mountains and remote regions of Central Asia - even with the ability to download map layers on these maps for offline use (but their satellite imagery is useful for researching routes ahead of time).

Do you already have a map app that you are confident of? There may be several reasons why you should not be so confident, especially if you are exploring or going on a route with limited information available.

If you are going on some of the more complex and difficult treks, you need to know that many map apps have serious drawbacks.

Map apps that can be used offline on your phone are mandatory, as you will have no internet data connection in the mountains. What you need is a map app that allows you to download a map of an entire country. Then, when in the mountains you will be able to see your position thanks to the freely-available satellite GPS signals. The ONLY map data source that is both up-to-date and somewhat comprehensive for the mountainous regions of Central Asia is Open Street Map data (which we comprehensively edit in certain regions).

So you need to use an app that relies on Open Street Map data.

What about your favorite map app? Your favorite map app is likely less useful for exploring Central Asia. Many map apps rely on amazing mountain map data made available by governments, private companies, organizations, volunteers and clubs. But this is usually only helpful in countries like Canada, US, Switzerland, Japan, New Zealand, etcetera. In Central Asia, it has to be a map app that uses Open Street Map data.

Does your offline map app use Open Street Map data? Almost certainly. 100% of the time when I’m told by somebody that they have found a map app that has the best mapping of Central Asia’s mountains, it is an app that does nothing but download the free Open Street Map data and display it to you. These apps are usually clear (in the small print) about the source of the data.

Unfortunately, many of the most popular map apps are very out of date in regards to Open Street Map data (despite their claims of regular updates). Some of them are almost a year out of date, some of them don’t update at all after you instal them and many of them do not integrate all Open Street Map data, leaving out vital information (for example, some show just a trail line crossing a river, but leave out the label that shows either a bridge or a ford through the water). Some map apps are clearly intended only for use in English-speaking countries and/or western European countries.

As of 2025 I’ve tried out well over a dozen map apps and only the OsmAnd app has all the features I want in Central Asia’s mountains. Not all apps that use Open Street Map data are equal, beyond just the issue of not integrating new data and map edits.

One problem with map apps that use Open Street Map data is that OsmAnd will show the trail quality, with seven different grades (for example, closely-spaced dotted line for good trails, far-spaced dots for bad trails and routes off-trail over open terrain), but non-OsmAnd maps just show the same style of line every time, and they don’t distinguish between clear, high-quality trails and trails that are so bad as to barely exist (or not exist, in the case of routes over open terrain). For now in Central Asia, it’s mostly just in Tajikistan where trail quality is integrated into the trails displayed. But this may change in the future…

Another problem with non-OsmAnd map apps is that some of them take Open Street Map data on rivers and streams, but unlike OsmAnd many of them do not differentiate between a stream and an intermittent stream. In OsmAnd, an intermittent stream is not a solid blue line, but rather a dotted blue line. Some other map apps don’t make a distinction, and show only solid blue lines. In drier areas this can give you the false impression that you can find water, when it is usually during the trekking season that these intermittent streams go dry.

My strongest dislike for map apps that are not OsmAnd are the fact that most of them do not show ‘farmyards‘, an Open Street Map category that includes shepherd camps, corrals, and overnight stops for livestock. One bad interaction with shepherd guardian dogs and you will very much want to know exactly where these ‘farmyard‘ locations are (not just due to fear of dogs, but also to know if you are drinking water right downstream from a large shepherd camp.) Also, if you are in trouble, then you will want to know where these ‘farmyards‘ are, as you can be helped at a shepherd camp (note that shepherds cycle through various camps throughout the season, so usually 1/2 to 2/3 not be occupied).

For some reason, many map apps don’t display cliffs like OsmAnd does. The topo lines don’t always let you know that a cliff is coming.

Other important features that don’t get displayed on many map apps: drinking water stand pipes/spigots, wells, livestock watering sites (troughs, bucket, small ponds, etc.). The maps generally always display natural springs, but not the other water features above (which can be very common throughout the region). OsmAnd displays all of these (if you have the display settings set accordingly).

But again, the map apps not being up-to-date is their worst feature. You may look at a mountain range in your map and see no trails or road or bridges or even villages. But with an up-to-date map app you may find that Open Street Map editors have added roads, villages, bridges, etc…

OsmAnd will display all the names, including the names of shepherd camps, orchards, meadows, gorges, shrines, etc. Many of these features are nor displayed with names in other map apps. These are useful for navigation and chatting with locals for up-to-date info.

I’m sure your favorite app looks better visually, feels better and has features that are better in some ways than OsmAnd. And OsmAnd probably feels like one of those tools that has way too many manual settings and doesn’t function as smoothly as other options. But when you want to not die in the mountains, OsmAnd is better. So maybe bring your favorite map app, and have OsmAnd on the side just on case you need it for all the reasons given above.

I change my mind on occasion, even about products, gear and tools that I have used for a long time successfully. If they lose their quality or have a terrible redesign, I will look elsewhere. If a new product comes along that is better, I will switch. So I keep an open mind - and I know that sometimes I fall behind and become out of date. So it is possible that sometime in the future - or even possibly right now (2025) - there may be a map app that does everything that OsmAnd does, but better.

What apps, aside from OsmAnd, are not highly deficient? It’s been a year since I downloaded and tested as many maps apps as I could (Mapy.cz was the best app aside from OsmAnd). Perhaps some of them have improved, or maybe one of the map apps I didn’t test is actually OK. Anything is possible…

Limits to apps using Open Street Map data

The map data relies on volunteer map editors, and the system is far from perfect. Volunteer editors have ignored certain regions, and there is little in these places to help you aside from the elevation/contour lines. In those cases you need to look at satellite imagery - which itself has its own limitations (very out of date - sometimes by more than a decade, cloud cover blocking the view, snow obscuring everything, low imagery resolution in some areas, no dates provided, etc.).

Name changes and styles. The Tajik government loves handing out new names. Place names are always in flux. In the past this was only in regards to towns and villages. But in 2023 they did a massive sweep of natural features. Read here for more info. Fully integrating that into Open Street Map data is a full-time job, and we don’t have the time for that. In Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan there are multiple competing styles of transliteration and naming conventions (example: Gulcha, Gul’cha, Gulcho, Gülchö). There is no standardization yet on the Open Street Map data for Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

Out of date satellite imagery: Open Street Map does not have a budget for recent high resolution imagery to use for mapping. That sort of imagery is extremely expensive, and hidden away as proprietary satellite imagery for use by corporations and governments with large budgets. So, some imagery used to edit a map is out of date. A bridge that an Open Street Map editor traced from satellite imagery and added to the map may have collapsed. I’ve been lucky, as all the times I arrived at a collapsed bridge in the middle of nowhere I was able to find a replacement bridge that had been built elsewhere in the area. But others have experienced worse luck.

Conflicting satellite imagery: The positions of objects across various satellite imagery sources are sometimes the same, and sometimes in conflict. Open Street Map editors may choose a layer to draw a road or trail on that is the least accurate of the choices available. In the worst case scenario I’ve seen gorges in steep terrain that were about a hundred meters apart on different satellite map layers.

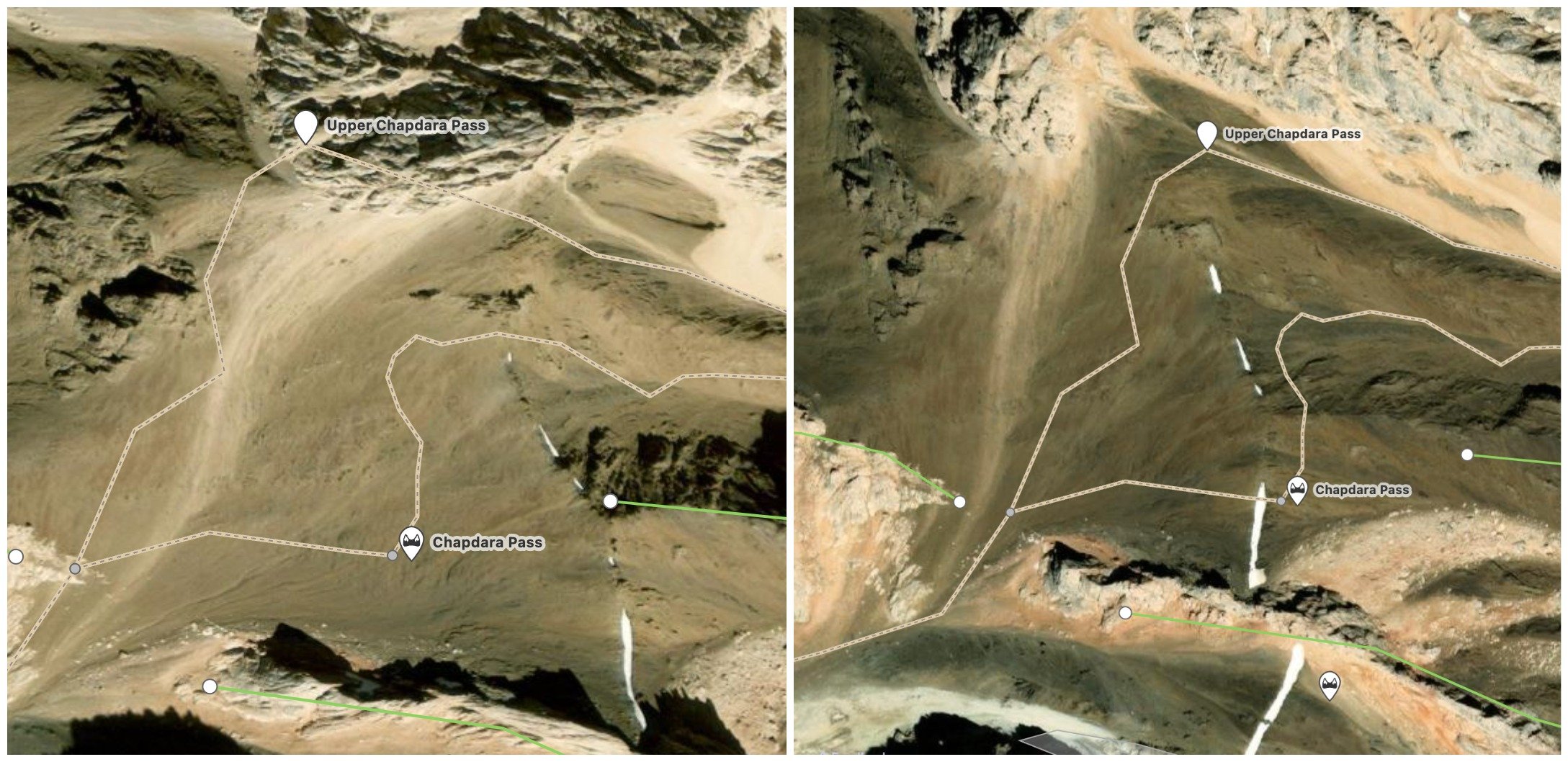

One of the more extreme examples I can find, from Open Street Map editing, while switching between two different satellite imagery layers:

The tracks and the passes in Open Street Map data in the two images above are in the same places, but about 100 meters apart on the actual images, despite this high saddle being fairly wide open with a clear view of the sky. What going on? I don’t know, I’m not a satellite imagery, GIS and GPS technician. Which pass location is correct? The one of the left, or the right? You’ll find out when you get there… This won’t be a problem here, as the wide scree slope is easy terrain and you’ll figure it out when you see the obvious low saddle. I now know the Open Street Map data is correct here thanks to two different Russian climbing teams that passed through here while recording GPS tracks. But in other locations it can be a serious problem and send you to a dangerous area. Use your own judgement when your GPS position is telling you something that doesn’t seem correct.

“Fake” trails: Sometimes you see a trail on your map app, and it does not exist. The source is Open Street Map data, but it does not exist or is ultra-dangerous when you arrive for your hike. Why? there are several explanations. 1. The satellite map imagery used to trace the trail is out of date by a decade or more, and the trail is grown over or faded from not having been used. 2. Open Street Map editors have traced an ibex trail, and when you get there you figure out that only an ibex could walk such a difficult and dangerous “trail.“ 3. The source is the old GenShtab map, which can be over 100 years old. 4. The trail on the map is a “route,“ not a trail. It’s a route over open terrain with no visible trail. 5. The trail on the map has as it’s source a GPS track from a hiker who may have travelled over open terrain in a wandering/lost pattern that is not the optimum route, and it’s not marked as a non-visible route. 6. It’s a “shepherd trail“ and you can’t believe that any person could actually do the trail. I have followed these guys, usually goatherds, and I can confirm that they are in fact walking some insanely dangerous trails where a single slip equals death. 7. The trail has as its source a GPS track from a climbing team.

Trails versus routes: This is a difficult one. It doesn’t seem that the Open Street Map feature that allows for editors to add a trail that has various levels of visibility, all the way down to pathless, has caught on with the “end user“ (the image below is a screenshot of the choices an editor sees when adding or editing a trail). These grades of trail are only shown on the OsmAnd app (of the apps I’ve tested), and misunderstood elsewhere.

The option of “No: pathless“ is needed in areas where the trail disappears completely, but there is still a “route.” For example, when the trail enters a wide open meadow or goes through gravel or sand next to a river. This is also needed when crossing rocky areas like talus and live scree. But many people are expecting to find a visible trail when they see the dotted line in their map app. Eventually they learn that trails often appear and disappear and then reappear again in Central Asia.

Fixing all the problems mentioned above would be a huge, long and expensive task, involving large numbers of people visiting mountain ranges around the region over several years. It’s not going to happen.

Inaccurate contour/elevation lines:

The source of the contour/elevation/topo lines on your downloaded map in Central Asia is the free data provided by NASA, ESA and (maybe) JAXA, and in other cases paid data from private satellite/GIS companies. This data can be not entirely accurate, and it varies worldwide. And it varies from app to app, depending on the source. There are also some “artifacts“ - on one of my contour/elevation/topo maps there is a 3000 meter spire next to the town of Rushon. Unfortunately, it does not exist (it would be by far the tallest sheer vertical drop in the world).

In general the inaccuracies that will concern you the most are about slope steepness. In some areas the contour lines show a slope that is an easy gradient, but is in fact way, way steeper than displayed. In one area I hiked, an easy downhill gradient was in fact a 100 meter tall cliff (with the satellite imagery not showing that clearly). Nothing is guaranteed until someone visits an area and provides a clear report, or in the case of the cliff, adds a cliff line to Open Street Map data (that some map apps don’t display).

Warnings about GPS Navigation

It has become clear that many hikers with plenty of mountain experience are not actually well-trained on GPS navigation. Search and rescue teams worldwide have reported higher numbers of rescues, with smartphones and GPS devices taking the blame. I have personally met and talked with more than a few hikers who don’t understand how their GPS signal can mislead them.

GPS location is not entirely accurate under the best of circumstance (a perfectly flat area with no obstructions and an open sky). But with tree foliage it gets worse. And in a narrow slot canyon you no longer have GPS signal. In a deep gorge the signal can be bouncing and put you hundreds of meters from your actual position. On steep north-facing slopes your position can be off by almost as much. Even in reasonably open terrain I have recorded a GPS track going up and down a mountain on the exact same trail and yet the GPS track round trip shows me sometimes 20-30 meters apart (and a location 20-30 meters from the actual trail could be deadly).

A scenario: I record a GPS track across open terrain. The route goes across a steep north-facing slope. It’s is a relatively easy route and I don’t need to use my hands on any rocks for balance. I have no worries about falls. I just need to pay attention to foot placement. I later pass on the GPS track or upload it to Open Street Map as a “no:pathless“ route. Someone then attempts the same route - following my GPS track or the route I’ve added to Open Street Map (which then appears on your offline map app). They follow my route exactly with GPS (blue dot right on the GPS track/trail). They then report it as very difficult and dangerous (despite having recently been in another area with many places much more difficult that they didn’t report as difficult). What happened? They were nowhere near where I walked. They were either farther uphill or downhill. Probably as far as 50 meters away, obeying their GPS. Why? Because GPS is inaccurate, especially on steep north facing slopes.

Use common sense and your own judgement. If you are sitting in a cafe and your GPS position shows you standing in the middle of the street outside, where are you? In the cafe or in the middle of the street? If you are in a gorge walking riverside and your GPS position shows you to be in the middle of the river. Where are you? Hiking on the trail or swimming in the middle of the river? When you get to that steep slope with no visible trail, don’t blindly trust the GPS - choose the route that makes the most sense to you, and don’t go crawling down a steep rock bluff.

Recommended Apps and Tools

This project edits the free and open source “Open Street Map” data (as do many volunteers elsewhere), which is used, by varying degrees, by numerous map apps. We recommend to download the offline map app "OsmAnd" to your phone and download the offline map of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, etc. However, to get the features necessary to survive a serious exploration in the mountains in this region, you need to upgrade the app with the "OsmAnd Live" upgrade (also referred to as “Annual All-Inclusive”). Other map apps are OK for doing a popular route, but far less useful for exploring.

Download the OsmAnd map app.

Pay for the upgraded version.

Download a country

Download contour lines

Download hill shading (“Heightmap“)

Pick your favorite map style in the “configure map“ settings (mine is “UniRS,“ as I can see trails more easily)

Set up automatic updates (I do daily; you’ll need it less often). Do a quick manual map update right before you leave for your trip.

If OsmAnd is too difficult to use, then you need to learn to adjust the manual settings for how the various map elements display.

You should not go to the mountains of Central Asia without OsmAnd (available for both Android and iPhone). It's free, but you will need to pay for the upgraded version "OsmAnd Live." These upgraded versions of the app have unlimited map downloads, elevation/contour lines, and regular updates available. The free version is NOT UPDATED after you install it. We and others are regularly updating the Open Street Map data, and there may be a very important update in there (example: a valley may be closed by a mining company, a bridge may be destroyed or a new one built in a different location, a mountain guesthouse has been opened or closed, etcetera). If you like to use topographic/contour/topo lines that show elevation, then you will need the upgraded version of the app. Try to download the contour map somewhere with good internet - Tajikistan, for example, is almost 600MB in size (versus 30MB for the regular map).

Unfortunately, OsmAnd is not as clear as some other apps. Sometimes it is hard to easily make out and select features on the map. But it is necessary. Tip: Go to the “configure map” setting and then go to “Overlay map“ and and play with the transparency settings (try “underlay map“ as well). This will make the map easier to read when you are following a trail through the contour/topographic lines. But it will also make some places, notably stores and guesthouses, invisible if you push the transparency slider too far to one side. At the very least, experiment with the map app before you go to the mountains.

So perhaps you should, at a bare minimum, continue to use your favorite map app while also downloading OsmAnd to use at the same time.

Supplemental map apps

If I’m planning a visit to an area with no trip reports or clear information available, I like to use the Google Earth or Google Maps satellite view (but, while you still have internet, you need to zoom in and cache all the areas you plan on looking at the satellite map while hiking). Apple Maps is also very useful for its detailed satellite/aerial view (but again, you need to cache an area while you still have internet). This is helpful for if/when you need to change your planned route.

Google Maps is good for when you have a signal and data and are researching hostels, hotels, guesthouses, supermarkets and restaurants in the cities and larger towns in Central Asia. But I have learned that some local people in villages have added hotels and guesthouses that don’t exist. So look for some actual trip reports or Google Maps reviews by foreign tourists to confirm it’s real. Some of the local reviews just translate to, for example, “my village is the best“ and “cool,“ while a hotel name translates in one instance to “this is my house“ (presumably an attempt to create a personal private bookmark/pin) Other places have been added as a joke, such as this one (by foreign tourists).

Generally I only ever use these supplemental app while staying at a guesthouse while on wifi and planning a new route or changing an existing one. I don’t use these to navigate while in the mountains.

Offline supplemental maps

For viewing a large area, “Russian Topo Maps Pro“ is nice (Android only, and only for people who can read Russian). But don’t trust the map source, as it is the “GenShtab“ maps (more info below). They are only good for viewing physical geography (but with glaciers many decades out of date). I no longer use this, as it’s better as a tool for trip planning on a desktop computer (see below).

Another useful offline map option that I have on my phone: Organic Maps for the cities and road travel (it is very simple and clear and easy to use - it’s a Maps.me fork app minus the extreme invasiveness of Maps.me).

Desktop research tools

If you are planning a route in the United States, you have good tools such as Caltopo and OnX. But they are not so special outside the US as they are in America (where their strength is showing private property and having access to various types of US government maps). But internationally it usually just comes down to using the Open Street Map layer, or a map that is using Open Street Map data. You can draw a planned route on numerous map websites/platforms and then upload the file you create to a map app on your phone for use in the field (after, of course, finding a tool online to add elevation data and a fake time stamp so that it will work on your mobile map app of choice).

For quick research and switching between various map layers (Open Street Map, Google, ESRI satellite, Russian topo maps, etc), I use Nakarte.me. It’s not so good for drawing GPS tracks (the track drawing tool does not automatically “snap to“ trails and roads), so I still use other options for that. It also has an option to display Westra’s database of mountains passes (a Russian database that goes back to Soviet times). Once you display the pass icons, you will know, in general, which passes are impossible for you as a hiker. Learn to identify the Russian Cyrillic letters A and B (Б), and then read this article about pass ratings.

A common question among trekkers and hikers planning a trip to the mountains of Central Asia is concerning snow cover - “Will Area X be free of snow on this date?“ These questions are sometimes worrisome, especially when phrased in a way that show the person asking the question is unaware that snow levels in the mountains can vary heavily from year to year, and that it can snow in the summertime at higher altitudes. The best you can do is look at a range of years on certain dates in certain locations and view the snow cover. You can do this in the Copernicus Browser - a collection of low-resolution satellite imagery going back almost a decade. The browser is not very user friendly and takes a while to figure out. Note that the Open Street Map layer is about 5 years out of date for some reason, and it’s been since then that extensive editing has been done in Tajikistan’s mountains. The old data barely shows anything in the mountains. To find an exact location you want to view, you can paste coordinates into the search bar at top.

What about GPS tracks? This project is about permanently editing maps, we rarely provide GPS tracks. If you want GPS tracks, search online on the various GPS-uploading websites (which have very few tracks outside of the most popular treks in the region). GPS tracks are fine if accompanied by waypoints with good info (on bridges, fords, springs, camping spots, etc.). GPS tracks that go with a written guide are also fine, such as those for the Pamir Trail or even a detailed trip report as for the Aku-Suu Traverse, for example.

What about my battery life? What I do in the mountains is carry an external battery pack (power bank) to charge my phone (I do not use a mini solar power charger due to reliability issues). But I still try to conserve battery as much as I can. All phones have a low-energy or battery-saving setting. Turn it on (or even just airplane mode). And quit the app when you are not using it, as running GPS in the background like some apps do runs down your battery. And maybe turn off your phone overnight. Note that your phone has a feature that lets you see what apps and functions are using the most battery.

Try to memorize or write down on paper the sections ahead of time (example: "stay on this side of the river for 5km, then cross over footbridge, go 3km up the opposite side of the river until the shepherd's camp"). You don't need to stare at your phone screen all day long, but check your position occasionally to make sure you haven't taken a wrong turn and followed a sheep trail to nowhere.

Don’t expect every mountain guesthouse to have reliable electricity overnight. For trips up to 7 days I have a 20,000mAh power bank. Longer than that I work hard to conserve battery (minimal photography and video work, no GPS track recording, etc.) or I carry another battery.

To play it safe, two 10,000mAh power banks are safer than one single 20,000mAh power bank (your could drop it in a river, it could die on its own, it could get fried by a power surge, etc…). If it gets close to freezing, sleep with the power banks (and your phone) inside your sleeping bag. And a sealable plastic bag or dry bag is good for protecting your batteries and electronics if you get wet from rain or a river crossing. As for quality, the Anker brand is very consistent.

Make sure your power bank supports 30W charging. And I don’t mean that the battery pack outputs 30W to your phone or other electronics, I mean that 30W is going to your power bank from the 30W charger. This takes some investigating, as manufacturers and sellers focus on telling you how quickly your battery charges your devices with how many watts (W), or “output,” but they often hide or don’t mention the info on how many watts their battery can “input” from a charger (important info for a hiker with limited time to charge their battery, and who may be competing with other tourists for limited electric outlets).

Bring a 30W charger. A regular charger (usually 5-10W) will take ~20 hours to charge a 20,000mAh power bank. You need a Euro plug, not North American plugs (if not in Europe, you can buy an Anker Nano 30W charger with European plugs from Amazon Germany or any European seller who delivers to the US/Canada/Australia etc.). You could just use a travel adaptor, but that’s adding a low quality item that can fail (or, like I’ve experienced, slip loose at an angle and stop charging). You should also have a 30W PD USB-C to USB-C cable so that your battery pack will actually charge fully overnight (the longer the cable, the better, some electric outlets are unreasonably high on the walls in this region). And an extra cable is always a good idea.

Do you just want a recommendation for a set-up? Sure, here you go:

Anker 537 Power Bank (24,000mAh)

Anker Nano 30W charger (European plugs)

Anker 643 USB-C to USB-C Cable

According to the manufacturer, this set-up above will allow you to recharge a dead 24,000mAh battery in 3.5 hours. Note that sellers sometimes don’t mention the Anker model number (537, 643, etc.) so you may need to compare specs from the Anker website to whoever you are buying from (if not buying directly from Anker). If you want to take my advice from farther above and combine two smaller power banks, then get two Anker Nano Power Banks (10,000mAh each) that support 30W charging.

Can you go higher than 30W? Sure. Look at power banks and chargers targeted towards laptop users. Generally you will see 65W charging input being advertised for that. Anker claims their 65W charger will fully recharge a 25,600mAh power bank (the “747” model in 2.5 hours). The main consideration for this is that the 65W charger will be significantly heavier (almost 4x) and bulkier if you are counting grams and ounces in your bag.

Final piece of advice: Make every person on your team download the map apps and an offline map. Try to imagine what happens if you, as the navigator, drop your phone in a river or down a ravine. You may need a back-up.

A request for updates: On most map apps that use Open Street Map data, you can suggest an edit or send a note to Open Street Map editors. It is phrased differently on different apps (“suggest an edit,“ “send a note to OSM editors,“ “correct a mistake,“ etc.), and sometimes the option does not appear until you create a bookmark/pin/point on the map. This note, once you are again online, is sent to Open Street Map and editors can see it. So tell them if a bridge is destroyed, add a new homestay, etc.

Paper Maps

Can I use a paper map? Sure, this will help save your phone battery. And paper maps are useful for longer trips - all the Russian and Ukrainian trekking/climbing expeditions who do the long traverses use them alongside their digital GPS tools (but they always have an assigned navigator on the team who is highly skilled). Reading and navigating from paper maps in the mountains is a skill. Not everybody learns it well.

Unfortunately, the details on most paper maps will be at a very large regional scale (except for the 1:100,000 scale tourist trekking paper maps available in Kyrgyzstan). In Tajikistan, my favorite for viewing the region at large are the 1:500,000 scale paper maps compiled by Markus Hauser (also available on Amazon: UK, USA, Canada, Germany, etc.). At the moment we don’t have an opinion or advice for paper maps in Kazakhstan.

Another option at a scale more suitable for trekking is to print out the old Soviet Military General Staff (GenShtab) maps that are available in scales down to 1:50,000 in some mountain areas of Central Asia. You can scour the Russian internet for a file and then have it printed at a printer who can print odd sizes/ratios - not a chore for a low quality street-side printing services in Central Asia. But you will then have to (a) be able to read the Russian alphabet, (b) make your own annotations on the map, and (c) know that these maps will get you killed if you trust them (more info on that farther below). While physical geography doesn't change much (except for the shrinking glaciers), the old maps may have bridges, trails and villages listed that no longer exist.

A much better option (if you can read place names in Russian) is to download and print the much clearer and updated maps from Slazav.xyz. You can print map sections from the Tien Shan, Fann, Alay and Pamir mountain ranges. These are the standard maps used by Russian trekkers and climbers in this region. Note: you need to get adjusted to seeing ridgelines drawn on the map as long solid lines.

If you want to draw, annotate or upload a GPS track of your planned route onto the map that you will print, we suggest searching online for free and paid apps and websites that can do this.

~

This is the end of the practical information.

You do not need to continue reading unless you want to know why so many maps are so inaccurate….

A history of fake maps and imaginary trails

Why are maps inaccurate? For some, it’s “garbage in, garbage out.” Many paper maps, including trekking and tourist maps, just copied the “Genshtab“ maps (also know as Soviet/Russian Military Maps). Some of the scans of the original Soviet GenShtab maps look nice. It's a beautiful old-fashioned color map created by the Soviet government for internal use (not for the public). It really shows well all the natural features. It gives you a good visual sense of the area you are in.

Unfortunately those maps (in Russian only), are out of date by 40 to 120 years, depending on the map section. So some “modern“ trekking maps show a trail that hasn’t existed since 1905, and a bridge that got destroyed in 1978 and was never rebuilt. Even worse, there are fake routes on these maps. I know, I’ve been on two of them. Local people - older people who knew the history of their region well, said these just don’t exist, and that they never have. Who added these fake routes? Well-meaning Soviet map makers using historical and recent sources from explorers added them. Unfortunately, some of these explorers were liars. In just one region of Tajikistan I’ve seen two accounts from modern-day Russian climbing teams who assessed that a route was never travelled in the past. In one case the liars were a 1960s Russian climbing team. The climbers lied because, likely, climbing was a competition in the Soviet Union and an expedition that won a category in the Union-wide climbing competition would get accolades and likely more funding in the following years to continue climbing. So as it turned out, one route was impossible, and another route took much, much longer than the 1960s climbers said - as they had never actually travelled it. They probably took a short cut once they got behind their planned pace (then made up a fake section report). Standard cheating athlete stuff with a dash of lying mountain climber. In another case a recent Russian expedition leader laughed about a historical explorer’s claim to have taken horses in a place that was seen to not even be fit for ibex. The explorer had clearly never been there. I’m sure this historical explorer returned to St. Petersburg or Moscow with some “maps“ based his incredible exploits. Later the well-meaning Soviet cartographer intern added the route to the map.

My personal experience was following the route through the Rosht-Jirkutal Pass on the GenShtab maps in the Pamirs. I got to the top of the pass and found a massive cliff on the other side. And yet a Russian explorer claims he went through here with horses. Perhaps a winged pegasus horse could make the cliff jump, but not a regular horse. The chance that some other saddle in the area may be the actual pass is more plausible, but a Pamiri guide came up here the same year and scouted out other saddles nearby, finding all off them to be difficult mountaineering/climbing routes. It could be that one of these secondary saddles is the proper route, but the glaciers on either side shrunk down, leaving a knife-edge ridge where it used to be a glacier-to-glacier pass that pack horse could pass. Whatever the true story, it has left the public looking at a map showing a route that is possible only for climbers.

Another example:

There is a “trail“ going through a “pass“ on the GenShtab map on the left, and the photo on the right is taken right below the pass by one of the first Soviet climbing teams (Boriskin, 1981) to successful pass through this pass. It is rated 3B in the Soviet/Russian alpine grade. This is obviously not for hikers, It is not a trail. It is not possible for anybody but a very experienced climbing team. Of course, I didn’t need to read the climber’s report to rule out an attempt to hike through this pass. The satellite imagery showed me the ice fall and the huge crevasses on the glaciers. But why this route was drawn on a map is a mystery to me.

“Do your own research“

In other areas it is not so obvious that a route does not exist and is not possible. For example, the Shitam (Shtam) Pass below.

A satellite imagery view doesn’t clear up much, as it could go either way: doable by a hiker or definitely not. I’m fairly certain this route and pass were added based on a Russian expedition about 120 years ago. I read their book, and they didn’t give any information about the passage across. The account is very unhelpful (“I went through the pass on this date“). Later, one Soviet geologist notes that this pass is for hiking but not for horses. Another geologist who hiked up to the pass from the east in 1962 described the other side as a “wild, terrifying cliff,“ and turned back. But in the guidebook “Tajikistan and the High Pamirs” there is an account of this pass, with a less detailed version online here (they spell it ‘Chtam’, making it hard to find). It’s clearly a steep pass that involves plenty of snow and ice. You can see the photo on the website of the two ‘hikers‘ wearing crampons (and I assume ice axes nearby).

I was able to slowly piece together enough information on this pass to decide against a trip there in favor of a better prospective pass farther south on the same ridge. You might be able to do the same for a route you are planning, but sometimes you can’t make a clear decision one way or the other. It’s just not always clear if a pass or route is doable or not.

Soviet names versus local names

Many of the local place names have been changed by the independent countries in Central Asia after the end of the Soviet Union. But aside from name changes and forgotten place names, there are placenames that never existed. I had a list of mountain river and valley names in one area (from the GenShtab map) and had about 20 shepherds, including one very old man who seemed to know absolutely everything about the area, say that these names have never been used, and that some of them sound like they’re not even from a Central Asian language (or even Russian). Then I met a retired professor of geography who was the local historian, and he said the same as the shepherds about some of the names on the map. Having spent time with enough shepherds, I imagine that when the surveyors and cartographers visited in the 1950s they so annoyed the shepherds with their demands for names for absolutely everything - including natural features that don’t have names, that the shepherds just started making up fake names for a laugh. Or the surveyors made up the fake names so that they didn’t return empty handed. Either could be true.

Are there reliable Russian explorers? Yes, more than a few. Lipsky and Vanovsky are both excellent. Their accounts and maps nailed the exact names (confirmed when I met people in these isolated areas), and when a route was not passable, they said so. But the Soviet cartographers weren’t able to filter the good from the bad.