Zulumart to Bartang High Route

Zulumart to Bartang High Route

This trek is a high route located in a very isolated section of the North Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan’s east. It is 50-70% off-trail and presents many challenges and dangers. If you haven’t seen our summary of Tajikistan’s high routes, read this first.

If you use the village of Qarokul as your start and end point then this trek is a loop (whether vehicle assisted or not). My plan is to not return east to Qarokul, but rather to head south to the Bartang Valley.

Every pass on this route below has been passed through by multiple groups. None of these passes are technically difficult (in the climbing sense), aside from the steep south side of Qurghonkul Pass. All others have gentle approaches and no serious dangers aside from snow, cold and elevation.

The red line is an old and mostly abandoned caravan route that was used (allegedly) from April to November (I’m skeptical of such a wide date range - check out seasonal snow levels on Copernicus). The yellow line is my suggested route. The blue lines are car roads. The beginning and end of the yellow route can be reached by any type of car from Qarokul (a 2-wheel drive can do these roads from Qarokul, no need for a 4x4).

You can start your trek from the Takhtaqorum (Takhtakorum) side or the Zulumart side, but I strongly suggest the western loop through Qurghonkul Pass be done clockwise (for reasons given below).

Note that on the map above Altyn Mazar is in Kyrgyzstan. You cannot start or end your trip there. There are no border crossing facilities here. If you see any online references to crossing here, they either date to the Soviet period when the international border here did not exist, or the crossings have been done by Russian tourists who get special treatment by Kyrgyz border guards (and they then must negotiate with Tajik border guards when leaving the country without an entry stamp).

Warning: I have created the proposed route based on dozens of trips that I could find reports for. I have not yet done this trip. It may be dangerous, or deadly (all dangers are listed below). You may have to turn back from a pass or river crossing. It is very isolated. You will be entirely on your own here. Below I go over the specifics of this are, but you should also read a general introductions to high route hiking in Tajikistan.

Season: The season is restricted by two factors: early season snow on the passes, and high water in the rivers mid-summer. It’s best to do this trip starting sometime at the end of August or beginning of September.

How many days? I have no idea. I’m planning for two weeks worth of food.

Transportation: I plan to have a driver from Qarokul drop me off on the west side of Qarokul Lake. At the other end I will just walk down the road to the Bartang Valley and find transportation eventually. There is no way to accurately predict when you will come out the other side, so I don’t see arranging a pick-up ahead of time as realistic. If you have a satellite phone, local language skills and the $$$ for a driver, you could call and arrange a pick-up from near Takhtaqorum. You may get super lucky and pass by a shepherd camp when they are being resupplied. You can then negotiate with a driver who will, I assume, be headed back to Qarokul or Murghob. But some camps go many weeks without being resupplied.

Zulumart Pass

Zulumart Pass is rated 1B on the Soviet/Russian alpine scale. The height is given as 4895 meters on older Soviet maps, but 5140 meters on newer topographical maps that have as their source the far more accurate Shuttle Radar Topography Mission.

It is Zulum-Art, not Zulu-Mart. “Art“ is a less common Turkic word for a mountain pass (with ‘bel‘ in Kyrgyz being far more common). Zulum is a place name that refers to the broader mountain range in this area of the north Pamirs. If Kyrgyz dictionaries are to be believed, Zulumart means “Oppressive/Violent Pass.“ But with that word (zulum) being of Arabic origin, it’s very doubtful that that’s its meaning. Old place names not based on personal names in obscure areas have as their origin Old Turkic or indigenous Eastern Iranian languages.

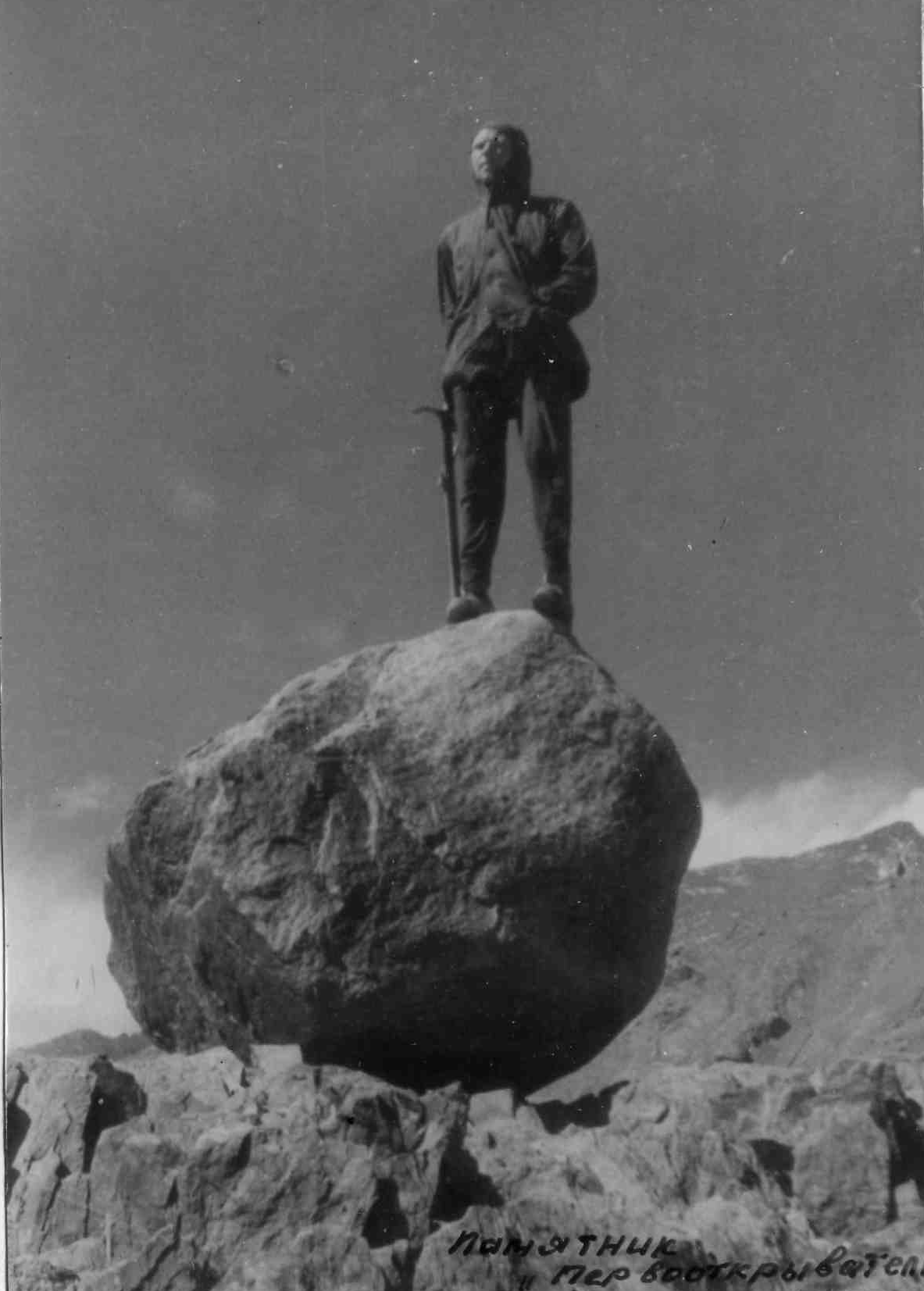

Zulumart Pass appears on historical maps of the area, but is a rarely used pass. Shepherds do not use this pass, and there is no visible path anywhere near the pass on either side. Climbers almost never use this pass as it is not a convenient location to access or exit the climbs and traverses that are popular. The last known group to pass through was the Britarov group in 1968. No other reports or accounts exist.

The pass is a scree saddle with a small cornice on the east side that appears to last through the summer. The only image that I could find is from the 1968 Britarov expedition, taken on September 1st, 1968 (see photo below). The caption at bottom reads “Zulumart Pass from the Sarigun River Valley.“ Sarigun is the river on the east side of the pass. Written in the photo in the center is “Central saddle“ and to the right is “Northern“ (the group notes that there are three saddles). The northern saddle clearly has a large and high cornice that would block a hiker. Of course, this is 1968 so it could possibly be much smaller now (see satellite images further below).

The Britarov group reported steep scree slopes and no glacier travel for the central saddle (and the glaciers nearby have only gotten smaller). The groups has little to say in general about this pass. If you can read Russian there is a link to a large ZIP of the report in TIFF and JPG files.

Regarding the cornice, recent satellite images from summer 2022 show that it was almost entirely melted by early August (see the four images below).

Comparing back over 6 summers, 2022 was drier in this location. Most years had a mid-August cornice that looked like the mid-July cornice above. So you will likely have to deal with a small cornice (going over if it’s not too tall, going up and around if it is).

What about fresh snow? I found one out of the last 6 years having a late summer snowfall in this area. The image below is Zulumart Pass on August 29, 2017. The south-facing areas have already melted the fresh snowfall away, but it remains on other slopes. This snow fell down all the way to 4400 meters. The same snowfall was seen in mid-September 2018. Compare this to 2021 when there was no snowfall until the first week of October. Based on the last 6 years there is a 1 in 3 chance of snow falling once from late August to mid-September.

Notable about this snowfall is that every pass on this route is above 4400 meters. That means that if you were doing this hike in 2017 you would have snow on every single pass in late August. How much snow? This area has very low levels of precipitation, and hunters visit the areas west of the Zulumart ridge well into November, traveling on light, dry and not deep snow.

Qayndi Pass

Qayndi Pass is a 1B-rated pass at 4790 meters (“Kaindy“ via Russian). The north side has a glacier, but it can be avoided with minimal effort. There is no visible trail on the approaches on either side. The Britarov group reported in 1968 that the old caravan trail in the Qayndi gorge was mostly faded away or destroyed, and that the only ones going up the gorge and through the pass were hunters and scientific expeditions. This disuse would, in my opinion, be connected to the Soviet-era construction of the Pamir Highway and other roads in the region. There would be no need for caravans to come this direction when goods can be driven by truck through the Kyzyl-Art Pass. And, since the end of the Soviet Union, the caravan route that used Qayndi Pass would be blocked by the Kyrgyz-Tajik border, which also blocks Kyrgyz shepherds from the Qayndi gorge. Expect nobody to be here.

K.K. Markov, a geographer, describes his 1932 trip in the briefest terms:

In the morning - the Qayndi pass, very high above the glaciers. The trail follows the firn. There are skeletons of horses and camels. We descend to the Qayndi River, a secondary tributary of the Muksu. It’s warm again. How wonderful smells of juniper, covering the slopes of the valley. In the west, Peak Communism is perfectly visible.

The Britarov group has nothing to say about this pass’ difficulty (meaning it was easy). A pass on an old caravan route is generally easy - if a horse, camel or donkey can do it (not counting the skeletons seen by Markov), then so can you. It’s not just the pass, but the river that is a hazard to pack animals as well. One geology team here in the late 1940s had a mule drown in the river.

A non-climber/hiker account of horses going through Qayndi Pass is from 1960, when a Soviet geological team came through here (with some difficulty), right after a group of Georgians hiked through the pass. And in 1968, a team of climbers (Molchanov 1968) travelled horses for part of their trip, going south to north through Qayndi Pass. On the left below is a view up the Turaqorum Glacier (which has now receded by 500-700 meters). Top right is a view to Qayndi Pass from the north (marked with an ‘X‘ in the photo), and the river crossing photo is from the lower Qayndi River.

Qurghonkul Pass

Qurghonkul Pass, or Kurgankul via Russian, is a 1B-rated pass at 4600 meters. It is on the same ridge as Qayndi Pass. You need to do this because you cannot “go around the corner“ up the Seldara River until winter. You will meet rivers up against very high cliffs.

There is only one detailed report on Qurghonkul Pass — by the 1986 Ustinovsky group. You can read the Google Translate version of the Russian article. Their elevation is wrong. It is 4600 meters on newer surveys, not 4900.

Expect very steep scree and maybe some scrambling. Plus, a difficult river crossing on the south side (more on that later in the article).

The Ustinovsky report noted this about the pass:

The second task was to determine the location of the Qurghonkul Pass. This is not indicated in the pass classifier guide, but we solved this problem by correspondence with employees of the Hydro-Meteorological Station Altyn-Mazar [note: this station is inside Kyrgyzstan]. It turned out that the Qurghonkul Pass does not require special [climbing] equipment. The most difficult part is the scree [on the southside] in the couloir with a steepness of up to 40 degrees. Employees of the Hydro-Meteorological Station and shepherds use it for the shortest exit to the basin of the Balandkiik and Fedchenko rivers. The grade in the list of high-mountain passes indicating a 2A grade indicates that those who submitted information about the difficulty of the pass to the main list either did not pass this pass themselves, or gave it an unqualified grade.

The Ustinovsky group’s passage without using any climbing gear definitely indicates that the earlier 2A climbing grade was incorrect.

As for shepherds and employees of the weather station, they will no longer be using this pass since the end of the Soviet Union and the creation of the international border nearby. Expect nobody here.

Image below: The Ustinovsky group in the saddle of Qurghonkul Pass, looking south.

Another group (Smirnov 1996) came through Qurghonkul Pass in 1996. However, their report makes no technical assessment of the pass. They merely state that they went through. But they do provide two photos (below), one of which shows some (slightly blurry) rope-free scrambling over loose rocks.

The photo below shows the northern approach to Qurghonkul Pass. The photos below were taken in the last week of July 1988 by a Latvian team as they hiked up the right bank of the Qayndi Gorge on their way to a different pass. As this is still early season, you can see the snow accumulated from avalanches in the Qurghonkul Gorge still (as well as plenty of snow on the ridge top to the south).

Takhtaqorum Pass

Takhtaqorum Pass is a 1A-rated pass at 4525 meters. The Russian transliteration is Takhtakorum.

In Old Turkic, takhta means “board” or “flat”. And qorum can be rocks, gravel, or large talus (but has been borrowed for a more narrow definition by Russian geographers for stone runs). In this combination, Takhtaqorum means shale or flat-rock. The -qorum is the same as -koram in the far more famous Karakoram.

It is the easiest pass in this area, and is used by shepherds (including families and children), hunters and kayakers. The kayakers carry their boats through the pass and put in on the Balandkiik River with the Musku River as their destination.

As a side note, do not set large bonfires in the ‘tugay’ forest along the rivers like the kayakers do. These forests are very rare here and provide a little island of shelter and food for the wildlife. Aside from this, they are kayakers and do not provide much valuable information for hikers. Of course, the helicopter rescue of a kayaker with high altitude pulmonary edema is a good warning to take your time acclimatizing and to not rush to your destination, even through a pass that is only 4525 meters.

Photos below by Steynard: the north side of Takhtaqorum Pass, and further below, the south side.

*Road Building Update*

Sadly, it appears a road was bulldozed through Takhtaqorum Pass sometime in the last few years. Russian boaters drove through the pass in 2019 (at 1:20 in this video). A hunter’s photo shows a vehicle at the hunting camp on the Balandkiik River at 3930 meters (hunters call it the “4000 Meter Camp” or misspelled as the “Balankiik/Balankik Camp“). A kayaker’s video shows how ugly the road is through Takhtaqorum Pass (start at 21:30). The construction of this road (very likely by the local hunting company) is especially senseless as the international hunters clearly enjoyed the horse ride over the pass on the old caravan trail.

Alternatives to Takhtaqorum Pass

If you really hate roads and you don’t want to end your trip doing a freshly bulldozed road over the final pass, then there are some (difficult) alternatives. However, you won’t be able to avoid the section of the road that goes along the Balandkiik River above the hunting camp, just the section that goes through the pass.

One option you can see on the map is the Yangidavan Pass, just to the west of Takhtaqorum Pass. This 1A-rated pass sits at 4700 meters, 175 meters higher than Takhtaqorum. The north side looks easy, but the steep and narrow gorge on the south side looks very unpleasant, with multiple water crossings and scrambling over boulders. I think any hiker would regret their choice to go through Yangidavan Pass. If you are still curious, you can see photos and a description of this passage from Kelin 2012, Lebedev 2009 and Romanenkov 2022. A further obstacle on the south side is that you must then cross the Kokjar River to get onto the Bartang valley road.

A more realistic option is the Kokuybel Pass at the head of the Balandkiik River. This 1B-rated pass is 5010 meters. The Kyrgyz translation for ‘Kokuybel’ is “Terrifying Pass.” But that’s more so from the perspective of a shepherd or horse rider. And, like Zulumart, basic inquiries by academics ruin the fun. Kokuybel Pass more likely got its name from the mountains nearby and means “cemetery ridge/slopes“ (naming a river or area for a nearby cemetery - even a single grave — is common).

The approach from the west is a gentle slope and you can avoid the glacier (first photo below). The eastern side has a large cornice, is steeper and will be more difficult (the second photo below). This descent may not be possible for some hikers. Photos below by Steynard:

The photographer above gives no description of their west-to-east trip through Kokuybel Pass. But from the rest of the photo album it’s clear that they aren’t travelling with crampons or ice axes.

One report on Kokuybel Pass does exist online (in Russian): Popov 1959. The cornice in the pass is a serious obstacle, as you can see in the route they selected.

This view is from the east side of the pass, looking west. Photo taken on August 16th.

More recently, a hiker came to the bottom of the pass and took a photo of Kokuybel Pass from the east. This photo below was taken on 28 June 2014 by Dmitry Amanov. It looks like the route to avoid the cornice is still up and to the north.

River Crossings

If there is no serious snowfall or difficulties with elevation, then I consider the major challenge of this route to be the river crossing of the Balandkiik River just above the Fedchenko Glacier. Any river crossing in this area is a challenge, but that’s at the height of the summer. and I recommend a trip starting after August or later after the meltwater subsides.

The Ustinovsky group crossed the lower Balandkiik River on August 17th, 1986, but at that time there was a cable crossing that likely collapsed along with the Soviet Union. You can see the cable crossing as early as 1965 in a photo by the Petrin group from Tomsk.

At the height of summer nearly every river will be a serious or insurmountable obstacle. This photo of two people crossing together is not from the main channel of the Balandkiik, but rather just a smaller tributary: the Jaylovkumsoy River. The date is August 13th. Photo from the 2009 Mansurov group.

The upper Balankiik River is not much of an obstacle, as this August 9th photo by the 2009 Mansurov group shows. In some areas the river spreads widely and you can find lower water crossings (here, for example). However, numerous tributaries flow into the river and it becomes much larger in its lower reaches.

If you plan to cross the upper Balandkiik River, where is the best location? It may not be where the jeep crossing is. It could be in multiple locations. You’ll need to choose for yourself when you get there. But certainly the location will need to be above the confluence with the Jaylovkumsoy River. The 1974 Moor group was able to easily cross here on horseback (photo below). They reported, on July 30th, a significant water drop overnight when they crossed in the morning. The 1971 Timoshenko group crossed in the same location three years earlier, minus the horses. They did so with a rope for security (photo shows fast water up to the mid-thigh), and reported that the water in the rivers here rose quickly after early morning.

On July 20, 2022 at about 7am the Romanenkov group crossed the upper Balandkiik River about 300 meters downriver from where the Yangidavan river/creek flows in. They report it to be mid-thigh high and with a strong current. Photo below.

What is my plan for the lower Balandkiik crossing now that the cable car crossing is gone? Just below Qurghonkul Pass the Balandkiik River does spread out and braid. I plan to cross here after the summer melt has subsided. See satellite image below:

The most recent crossing in this area that I can find information for is from the 1996 Smirnov group that crossed the river after descending from Qurghonkul Pass. The photo below is three of the six team members crossing together (early morning August 20th). They note the depth of the water was 0.6 to 0.7 meters, and they crossed in an area that was 30 meters wide. They also note that there wasn’t a noticeable water drop overnight, but that they crossing was still “not particularly difficult“.

Why do I/you need to cross the river? Because there is a historical route along the left bank (south side of the river). The right bank (north side) is very rough and unpleasant and would take forever and be exhausting.

The lower Balandkiik River is really nice, as you can see in the photo below from Kristof Stursa:

The old caravan/shepherd trail along the left bank of the Balandkiik river (south side) is sometimes as high as 500 meters in elevation above the river gorge. This trail is very faint, and appears and disappears regularly. The tributary creeks and rivers here should not be underestimated. For example, see this description by the 1908 Kosinenko expedition (during peak meltwater season).

The path here is difficult, especially along the left bank of Balandkiik to Zulumart [i.e., until the Zulumart River joins the Balandkiik]. Due to the frequent steep ascents and descents along the way, now and then you have to correct the horses’ packs, as they all move out, then forward, then back. There are several difficult crossings, extremely dangerous, since the mountain tributaries of Balandkiik are real cascades: if a horse falls or stumbles, the death of the rider and horse is inevitable. After Zulumart the path improves, and the ascent to the Takhtakorum pass is quite gentle.

The middle section of the Balandkiik River is less scenic. However, as you can see below from the photos by the Popov 1959 group, there should be enough here to keep you from getting bored.

However, it is in this area where there is one scenic attraction near the river: the “Firuza“ springs, a calcium-carbonate rich spring that has created travertine mineral deposits over a large area. I’m skeptical of the name of these springs, as some scientists are attempting to name them the “Firuza Moscow State University Springs.“ These springs are downriver from an active shepherd camp, 100 meters from an international hunting camp and right next to a historical caravan route. They definitely have an indigenous name that is not yet on a map. Photos of the springs via Radio Ozodi:

Bridge over the Balandkiik

On satellite imagery you can see a footbridge over the Balandkiik river (link here). Well I think it is a bridge. It may just be a very, very straight natural feature. There is no updated high quality satellite/aerial image from this area to confirm it still exists. If there is a bridge, it is likely built by the hunting outfitter with a camp upriver.

Cable car over the Balandkiik

There is a cable car crossing over the Balandkiik somewhere near the hunting camp. You can see it in this video starting at 1:30. This belongs to the hunting camp. It will be of limited use to you as you will need to return the car to the side of the river where you found it. If the car is on the north side (right bank) of the river, don’t use it or you will strand whoever just used it. If the car is on the south side of the river (left bank), then try to get the attention of someone in the camp. Will they come down to the river and help you cross? Any mountain local would absolutely do this. But this is a hunting lodge, not a mountain village. So I can’t say for sure.

Why would you need to cross here? For me it would be to see the travertine formations around the springs (and then return back to the north side/right bank). The main route is on the right bank. If you try to go upriver on the south side (left bank) you will have to cross some major tributary rivers.

Can you just walk through the river in the fall season? It depends on the location. The Alexandrov 2019 catamaran group boated down the Balandkiik River starting on October 3rd. You can see what the river looks like in the video below starting at 1:30 and ending at 5:00. After that it is the Muksu River.

Qayndi River

The Qayndi gorge is much less of a worry for river crossings. But I have no detailed reports, but the Latvian expedition linked below reported no difficulties with crossing the Qayndi River (to avoid cliffs or bluffs on one side or the other), as opposed to the drama they faced crossing the Sauksay River to the north.

As for the name, a Ukrainian geologist points out that 'Qayndi’ means birch in Kyrgyz, so this name appears as many as a dozen times throughout the north Pamirs on other valleys and rivers with birch trees. But this one is the largest and most prominent.

The photo below is of the upper Qayndi River at about 3500 meters (ignore the 3800 written in the photo next to the line showing the route). Photo via the 1988 Latvian expedition. Expect much taller juniper trees and birch trees lower in elevation in this gorge. The Latvian team described the lower Qayndi Gorge as “amazingly beautiful, with tall grass, flower and juniper trees“ (but they save their camera film for the high climbing portion of the trip)

If you look at the route along the Qayndi River you may notice “Suyak Mazor“ marked on the map at about 3500 meters (location approximate, based on an old GenShtab map and my best guess from looking at satellite/aerial imagery). A ‘mazor‘ in this region can be a cemetery, a single grave or a shrine. This mazor is a single grave, presumably the grave of a shepherd or caravaneer. The only photo dates from the 1988 Latvian expedition (ignore the elevation they mark on the photo below). In the years since it may have degraded into a barely noticeable pile of rocks, so you may miss it.

Zulumart River

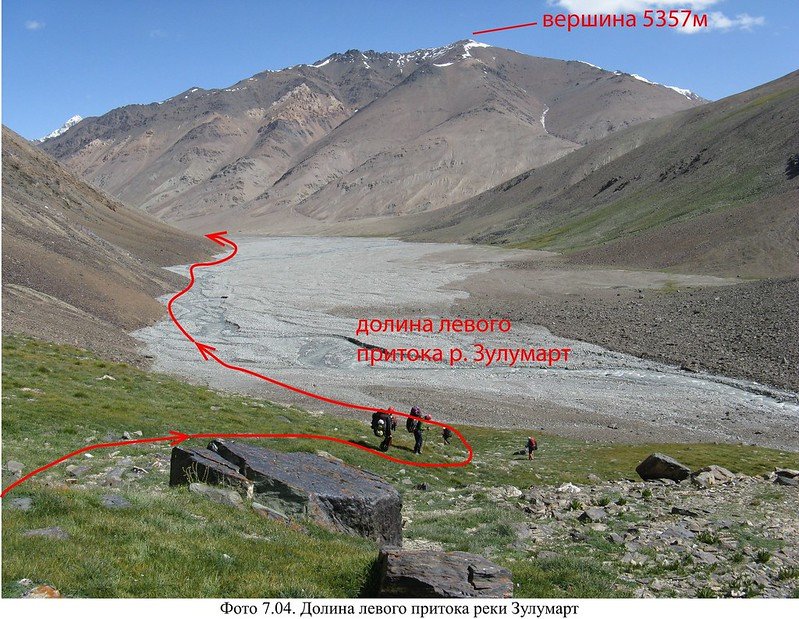

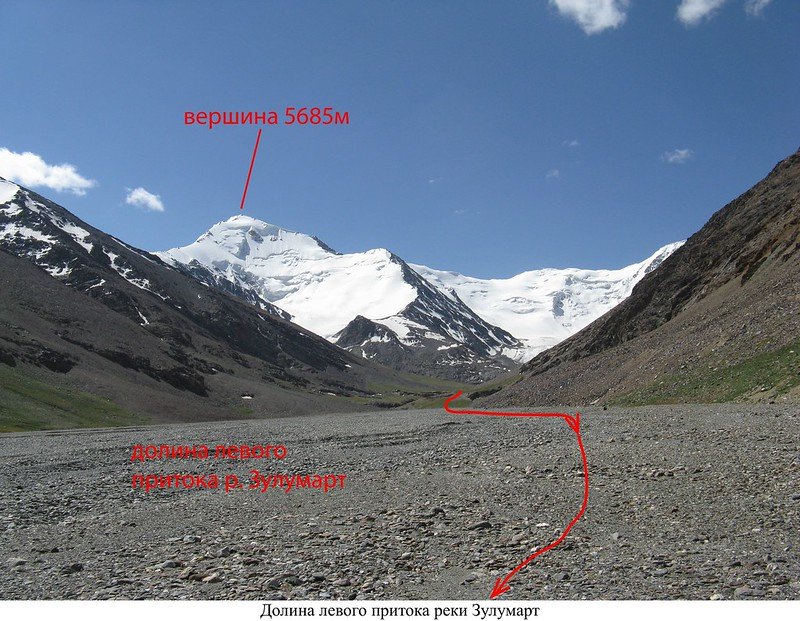

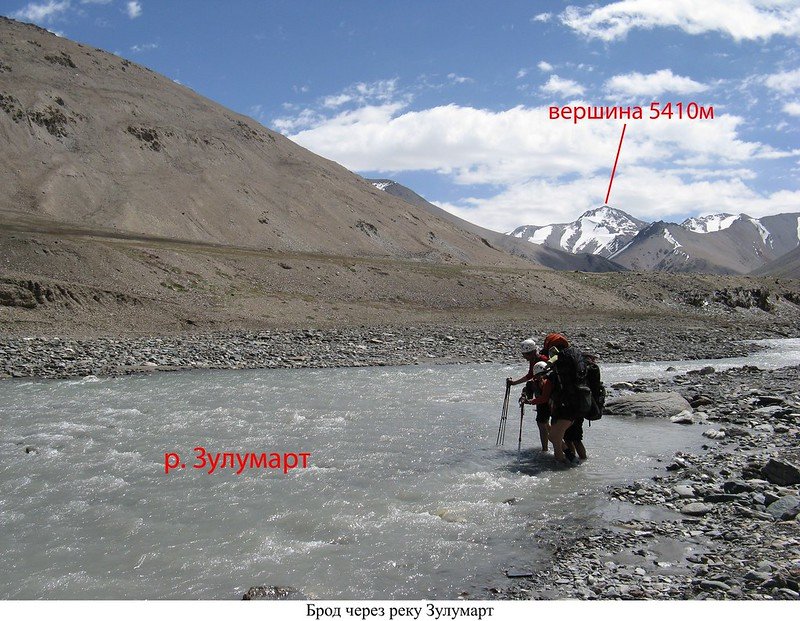

You’ll need to do at least two crossings, plus at least one tributary. It seems like it won’t be a problem. A Ukrainian team passed through the Zulumart Valley on July 31st and August 1st, 2012. They had no problems at all, as you can see below:

The lower Zulumart, however, is much more narrow. It will be more difficult to cross here when meltwater is at its peak in July and August, and you will likely be crossing the lower Zulumart at least once, and maybe even twice, depending on your route selection.

This photo is from August 7th, via the Mansurov 2009 group.

The Kelin 2012 team showed that the best views are in the side gorges leading away from the Zulumart River. This spot (above) is 2.5km up the 2nd left tributary, with minimal elevation gain.

Summary of Obstacles

In general, too much unmelted early summer snow on Zulumart Pass can stop you. High rivers in the July-August melt season can stop you in many places (with as many as 6 river crossings being hard to impossible in the high melt season). In low water you still may be stopped by the lower Balandkiik crossing. And if the bridge on the Balandkiik does not exist, you won’t be crossing the mid-Balandkiik. And, in any conditions, the rock and scree southern approach to Qurghonkul Pass may not be possible for you. I have made a PDF map of the main obstacles that you will face even in the best conditions, meaning no fresh snow and September low(er) water.

You can still do a hike if you get stopped at any of the obstacles. If you get stopped at the Zulumart River ford you can still do Zulumart Pass to Takhtaqorum Pass in either direction, but with skipping the western sections: lower Balandkiik River and the Qayndi Gorge. Look at the map and note the routes you can still do if you get stopped at any of these obstacles. For example, if you get past the Zulumart ford but then find there is no longer a bridge in the mid-Balandkiik River, you can go east-to-west through the Qayndi Gorge, get a view of the end of Fedchenko Glacier and then return the same way.

There are many options. But being here in September gives you the most options.

Fedchenko Glacier?

I plan to make a short side trip to the terminus of the glacier, but it depends on the water levels in the Qizqurghon/Kyzkurgan tributary river. The most recent (low quality) satellite imagery shows that it is braided into 6-8 channels right before it flows into the Balandkiik River (as opposed to a single channel that would be deep and swift). But in previous years it has been in two channels, and may be too difficult to cross even in September.

If you Google Fedchenko Glacier, you will see some remarkable imagery, but these are mostly taken by helicopter or by mountain climbers with a high vantage point of the mid- or upper Fedchenko. Don’t expect the same view. And note that the lower part of Fedchenko Glacier is mostly debris covered (rock, gravel, sand). The aerial photo below by Martin Mergili shows the terminus of Fedchenko. I plan to scramble up on the bluffs to the left and hope it’s high enough to get a good view up the glacier.

Mergili, M. (2010-2022): The world in images. Digital media (https://www.mergili.at/worldimages)

As for getting on the glacier, if you aren’t experienced with glacier travel, don’t do it. There is a memorial next to Fedchenko Glacier for a body that was found (and eventually identified as a lost member of a climbing group from decades before). And a mysterious bearded figure known as Yura, who identified himself as a traveller from St. Petersburg, surprised a geologist camp nearby with a nighttime visit to their camp in summer 1960 and then departed to the glacier, where he died.

Gear and Food Advice

Read our general gear, health and food guide for trekking in Tajikistan. For this route, I would definitely make sure to have at least a -15 Celsius sleeping bag and warm clothing. This is not the time to save weight by skipping the warm thermal base layers. I plan to wear very thick trekking pants and to bring winter or near-winter base layers, plus an extra fleece top mid-layer. I’ll be ready for brief periods in -5 to -10 Celsius with strong winds (worst case scenario for this time of year). This is probably boot terrain. I will also bring a pair of lightweight running shoes for the river crossings. As for food, I really don’t know as I can’t be sure how long this will take. I plan on 2-weeks worth to be safe.

Permits Required

You need a GBAO permit to be in this province, as does every other tourist. And you also need a Tajikistan National Park Permit ($10 per day) from the PECTA Office in Khorugh (but also read what I wrote about this permit in the introduction to high routes in Tajikistan). Do you need a special border permit for when you are in the lower Qayndi Gorge? Maybe technically you do. But kayakers have gone through this area a few times over the last decade and have never said anything about a permit. As for enforcement, there is nobody here on the Tajik side… as far as I know. In 2021-2022 there have been occasional border war conflicts between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, so who knows how that has affected this area if at all (e.g., if a new observation post was set up, I wouldn’t know about it until I’m there). If you are worried, then when you go down the Qayndi Gorge, take a quick left up to Qurghonkul Pass (and don’t go down further to get a view of the Muksu River). Kyrgyzstan has very clear and regularly updated border zone rules for tourists, complete with maps and an online permitting system. For Tajikistan it’s totally unclear until you unexpectedly meet the border guards. From what Russian climbers say about their meetings with border guards in other areas, the border guards don’t know the border rules either, and everything is “negotiable.”

Alternative trek: If this all sounds too dangerous, hectic, unpredictable, and isolated, then consider the safer and easier Bartang to Murghob high route instead.

Cultural, historical and economic context

The caravan route through this area was likely abandoned with the construction of the Pamir Highway through Kyzyl-Art Pass. There was no longer any need to take this difficult route. With the end of the Soviet Union there was a final blow to travelers and shepherds: the formation of an international border between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. For example, this Kyrgyz family below at a summer camp in the Qayndi gorge (visited by Molchanov, 1968) are from Daroot-Korgon in Kyrgyzstan. Summer grazing here in Qayndi is only possible from the Kyrgyzstan side, but an international border has ended that practice.

There are occasionally Kyrgyz border guards at Altyn-Mazar, but there are certainly no border crossing facilities here. Since independence the scientific research in the area was greatly reduced and the number of tourists (mountain climbers and boaters on kayaks and catamarans) also declined.

At the moment there are only a few shepherds in the upper Balandkiik Valley who stay for the summer grazing season. Russian travelers who have talked with them identify them as being from “Rushon,“ meaning they are Pamiris from somewhere in the Rushon District (i.e., Bartang). Elsewhere in the north Pamirs the shepherds are ethnic Kyrgyz. When you enter and exit this area you will meet Kyrgyz shepherds (east of Zulumart Pass and south of Takhtaqorum Pass). They do not travel over the passes into the Balandkiik area.

The hunting camp in the mid-Balandkiik Valley caters to international hunters who pay about $40,000+ per person for their hunting trips. All international hunting outfitters go through a single local businessman who has commercial hunting rights here (as opposed to the ANCOT hunting conservancies elsewhere). They hunt both argali (Marco Polo sheep) and ibex. The Tajik government gives out a limited number of hunting permits per year. Neither of these species are endangered (see wiki articles here and here). The main threats to these species were/are, especially in the 1990s: overgrazing by domestic livestock, hunting by shepherds’ guardian dogs, and poaching by local people (for meat, not trophies). Regarding current numbers, every year 45 Marco Polo hunting permits are sold for the Murghob Hunting Concession, a broad area with a population of 23,000 Marco Polo sheep counted in 2009, a massive increase from the 1242 sheep counted in this area in 1995. This does not mean that all areas have had their populations rebound. It depends on the area, with some areas declining “due to extensive habitat degradation caused by domestic livestock, principally domestic sheep and goats, harvesting of teresken for fuel, and poaching by local herdsmen and others“ (see article linked above). No studies exist for this exact area.

All the names in this area are Kyrgyz or Old Turkic place names that would have replaced the (now unknown) Eastern Iranian place names hundreds of years ago when Turkic people spread into Central Asia. One name here has been half Tajik-ized, and that is the Balandkiik River. ‘Baland’ means ‘high‘ in Tajik and ‘kiik’ means deer or goat, but not in Tajik. And ‘kiik‘ may be a Turkicized ‘khek‘ which is river in some Pamiri languages. But it may actually not be ‘baland‘ but a different word that when combined with -kiik means something like “[place where] goats allow themselves to be seen,” presumably in Kyrgyz. But this is now the official government-approved name for the river. There is also a layer of Russian names nearby, including Fedchenko Glacier and the many high-level mountaineering passes and peaks that were given Russian names.

Nobody has talked to the Pamiri shepherds about place names. They may have a separate set of names for this area.

To add to the confusion, someone in the capital city has recently renamed almost every place name in this area.

***

Can’t find the place names I mention on your map? Then switch to OsmAnd.